Have we made the wrong assumptions about the Good Samaritan parable and its context?

Was the lawyer who prompted the parable trying to trick Our Lord, and make himself look good – or something else?

Was the lawyer who prompted the parable trying to trick Our Lord, and make himself look good – or something else?

Editor’s Notes

The following mini-series is about Christ’s parable of the “Good Samaritan,” which is read on the 12th Sunday after Pentecost in the traditional Roman Rite.

It takes place towards the start of what Fr Coleridge calls “the preaching of the Cross” – during the later Judaean ministry, after the mission of the Seventy, and before Our Lord’s visit to Martha and Mary.

The occasion of the parable was a question from a “lawyer.” The “lawyers” are normally associated with the factions of the Pharisees and Scribes, and are awarded with two “Woes” from Christ in the chapter following this Parable:

Woe to you lawyers also, because you load men with burdens which they cannot bear and you yourselves touch not the packs with one of your fingers. […]

Woe to you lawyers, for you have taken away the key of knowledge. You yourselves have not entered in: and those that were entering in, you have hindered.

Many explanations of this parable present the “lawyer” as trying to catch Our Lord out, and to present himself in the best light – based on the Gospels saying that he sought to “tempt” Our Lord, and to “justify” himself. St Luke also tells us, in the following chapter, that:

As he was saying these things, the Pharisees and the lawyers began violently to urge him and to oppress his mouth about many things, lying in wait for him and seeking to catch something from his mouth, that they might accuse him.

However, the question that prompted this parable came before this, and before the “Woes” already mentioned.

Fr Coleridge, however, shows that this interpretation is based on several assumptions which are far from certain – and which may change our understanding of this whole incident.

The Good Samaritan

The Preaching of the Cross, Part I, Chapter XVII

St. Luke x. 25-37

Story of the Gospels, § 100

Burns and Oates, London, 1886

Have we made the wrong assumptions about the Good Samaritan parable and its context?

External rituals and theological debates are nothing without love

The Good Samaritan and using religion as an excuse for neglect

Our Lord in Judaea

St. Luke passes on at once from the passage on which we have been commenting to a series of anecdotes and instructions, between which there does not appear to be any certain connection with regard to time or place.

It seems obviously to be the aim of the Evangelist to give us in this series a collection of teachings of our Lord, belonging all to this period of His preaching, and all generally connected with Judaea as their scene. But he does not think it necessary to trace our Lord’s footsteps from place to place, with the same exactness as we find in some parts of His Galilaean preaching. In all this part of St. Luke’s Gospel there are but few notes of particular places, although it is indisputable, from the general colouring, so to speak, that the incidents must have occurred in Judaea.

We have come to a part of the history of our Lord in which the narrative is far more concerned with what He taught than with what He did, and this remark applies even to His miracles, of which, as has already been said, we have but very few in this portion of the third Gospel. It is quite possible that St. Luke, according to his wont, follows accurately the course of time in every single particular in these chapters, but it does not seem all-important to insist on this.

We may safely assume that the whole of what is here related belongs to this period, when our Lord was preaching first in Judaea, and afterwards, for some time, in the region of Peraea. The first incident of this collection is certainly important enough to have been placed first, even if it did not precede the others in point of time.

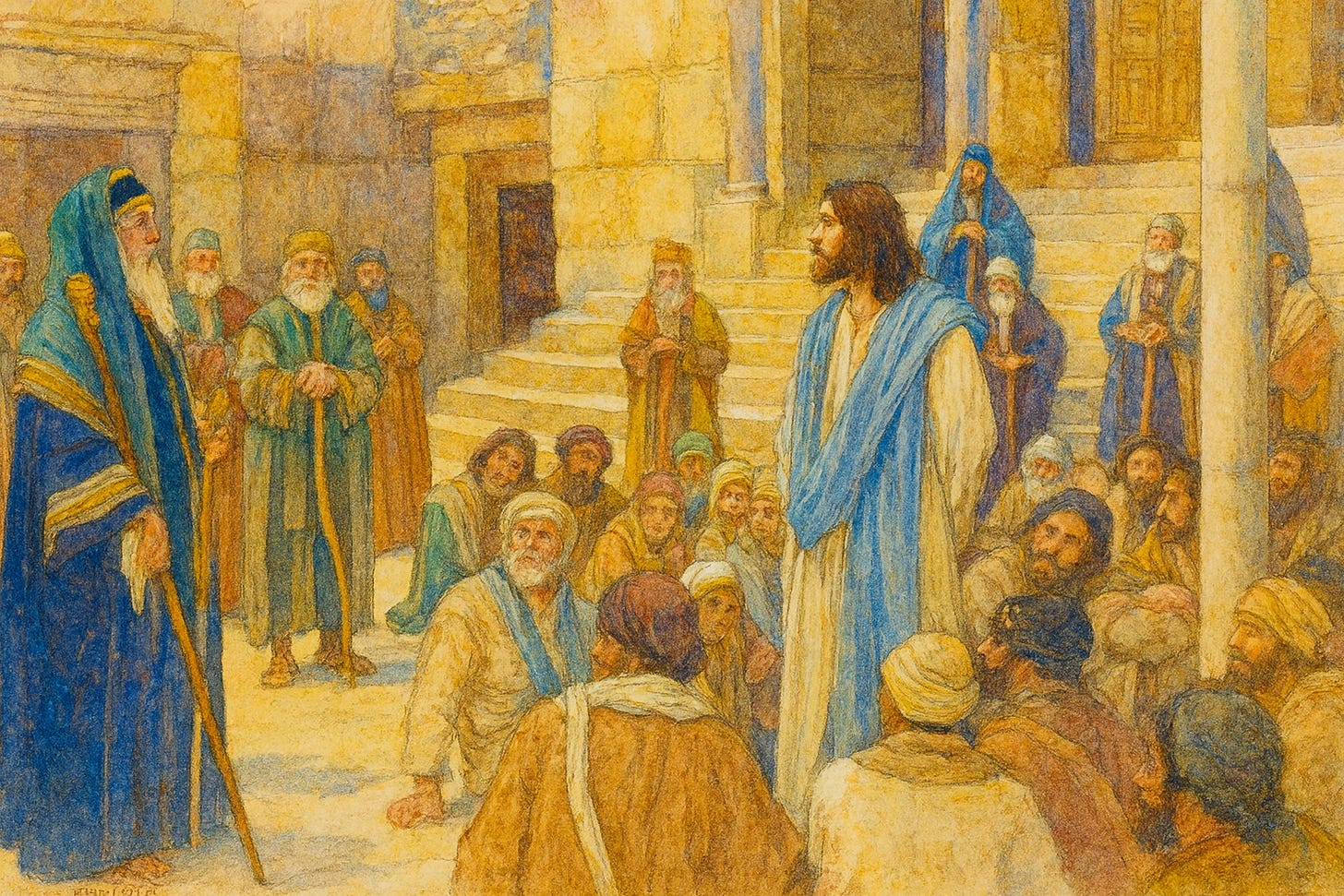

Question of the Lawyer – not malicious

‘And behold a certain lawyer stood up, tempting Him, and saying, Master, what must I do to possess eternal life? But He said to him, What is written in the Law? How readest thou? He answering said, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart and with thy whole soul, and with all thy strength and with all thy mind, and thy neighbour as thyself. And He said to him, Thou hast answered right. This do, and thou shalt live. But he, willing to justify himself, said to Jesus, And who is my neighbour?’

There are naturally various opinions about the intention and spirit of this lawyer or scribe. Some think that he asked the question in malice, in the hope of leading our Lord into some compromising statement, in the same spirit with the priests at Jerusalem, when they had brought to our Lord the woman taken in adultery. Others see in his conduct and in his language no reason for doubting that he asked the question in perfect good faith, like the young man a little later, who asked a very similar question.

We must not let ourselves be led astray by the language of our version, and indeed of the Vulgate, in which the word which answers to ‘tempting’ seems to imply a bad intention. This Greek word, with its compounds, does not of necessity mean more than to ‘make trial’ of a person. Thus when our Lord asked St. Philip the question about the procuring of bread for the five thousand, St. John says that He did it for the purpose of ‘proving’ Philip, for our Lord Himself knew what He would do. There could have been no malice in our Lord’s question, yet the Greek verb in that place is the verb of which one of the compounds is used in this place for the question of the lawyer.

Some questions may be asked for the simple purpose of information, others for the purpose of entangling the person who is interrogated, others for the purpose of leading him into a contradiction, and exposing his ignorance, and others for the object of eliciting from him a declaration on some point which is at the time a subject of controversy and dispute.

It appears that in the time of our Lord there was a common controversy as to the class of commandments in the Law which were to be considered the greater, a controversy which some schools settled in favour of the ritual and ceremonial part of the Law, while others maintained the supremacy of the moral precepts. This seems to have been the reason for the question afterwards asked of our Lord on an occasion which is sometimes confounded with this, when He was asked what or of what kind was the greatest commandment. But we do not seem now to have to do here with a moot question of this kind.

There is no reason, unless it be conveyed in the use of the word tempting, of which we have already spoken, for supposing that the question of this lawyer was asked maliciously. Our Lord does not treat the questioner as He sometimes treated those whom He wished to baffle, and the answer given by the lawyer in his turn was perfectly sound, and was praised as such by our Lord.

There may be a difficulty raised as to the second statement made by St. Luke concerning him, namely, that he asked the second question, for the sake of which and of our Lord’s answer thereto it is probable that the whole incident is related here, ‘being willing to justify himself.’ But with regard to this expression of St. Luke we may speak presently.

Answer to our Lord

The answer given by the lawyer is taken from two passages in the Pentateuch, and it shows his intelligence and study of the sacred writings that he should have combined them. The first part of the answer is found in the sixth chapter of Deuteronomy:

‘Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart and with thy whole soul and with thy whole strength.’

The rest is found in the nineteenth chapter of Leviticus: ‘Thou shalt love thy friend as thyself.’ In the original Hebrew, the word which we read as ‘friend,’ following the Vulgate, is translated by the Septuagint writers by the Greek word which means ‘neighbour.’ There is thus no difference between the texts, except that in the passage before us the description of the manner of loving God which is enjoined is fourfold and not threefold, the word which is represented to us by the word ‘mind’ being left out.

The answer shows that this Scribe was on the side of those who settled the question between the moral and ceremonial parts of the Law in the Christian way. He had the texts ready to his mouth, and we may suppose that the real difficulty which pressed him was the question which he goes on to ask, as to the extent of the commandment concerning his neighbour. For this reason we shall defer the explanation of the fourfold division of the love of God until it occurs more directly towards the very end of the public teaching of our Lord, where it is related by St. Matthew and St. Mark, St. Luke omitting it because he has already mentioned the question as raised in this place.

Here it may be enough to say that:

The love of God with the whole heart must mean the direction of the whole will with perfect singleness of aim to God, as the one supreme end of life

The love of God with the mind must signify the subjection of the whole range of the intellectual powers and faculties to Him as the supreme truth

The love of the soul should be understood as the service of Him by all the parts and operations of the soul as distinguished from the spirit, which embraces therefore the regulation of all the sensitive and natural powers in His service; while…

The love of God with the whole might or strength must represent the use of all the powers of soul and body alike, of which operations the whole of our external life is composed.

Having said thus much, we may add that the precept of this perfect love of God can be adequately and perfectly fulfilled only in the case of the blessed in Heaven, when the final glorification of the body shall have completed the adoption, as the Apostle speaks, of the children of God. For there alone will this positive precept be fulfilled in all the extent of which it is capable.

Nevertheless, it can be fulfilled and has been fulfilled by the saints on earth and in this state of pilgrimage, in that there has been in them no positive violation of the precepts by the use of the faculties of heart and will and affections and intelligence, or memory, or intention, or of the bodily powers and members, which has been directly contrary to the love of God, although there may have been some deficiencies and shortcomings from all that might have been done for the love of God.

Our Lord’s reply – and the question ‘Who is my neighbour?’

Our Lord answered the lawyer with loving courtesy and encouragement, ‘Thou hast answered well, this do and thou shalt live.’

He must have been speaking of the eternal life concerning which the lawyer had put his question. And then the inquirer came to what, as has been said, was probably the real question in his mind, his conscience perhaps troubling him with doubts as to the limitation of neighbourly love which was commonly taught, or at least practised, by the Jews.

‘But he, willing to justify himself, said to Jesus, And who is my neighbour?’

His desire to justify himself does not in any case imply that he wished in any bad sense to ensnare or tempt our Lord. It can only mean either that he felt in himself some self-reproach for not following out this commandment in its fulness, or that he wished to learn of our Lord the way in which he might make himself more perfect in justice by its observance.

For the word to ‘justify’ has this sense naturally, and does not only mean to make out a person as innocent against some charge explicit or implied, but also to make him just by an increase of inherent virtue, such as might be gained by any one who learnt from our Lord’s teaching some more lofty path of justice.

But what of the Parable itself? Fr Coleridge’s commentary continues in the next parts.

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

The Good Samaritan

Have we made the wrong assumptions about the Good Samaritan parable and its context?

External rituals and theological debates are nothing without love

The Good Samaritan and using religion as an excuse for neglect

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

I was taught that there are no stupid questions, in school. There are, however, stupid people.