The accusation you might miss in the Parable of the Lost Sheep

This parable is not just about God's love – it's also a condemnation of hirelings who should be shepherds.

This parable is not just about God’s love – it’s also a condemnation of hirelings who should be shepherds.

Editor’s Notes

In this part, Fr Coleridge tells us…

How the parable reveals the Sacred Heart’s joy in recovering a single sinner.

That our Lord’s mission of redemption was present to Him even in this gentle reply.

Why every detail of the parable may reflect the economy of salvation and the Passion.

He shows us that divine love is not content merely to forgive—it rejoices aloud and calls Heaven to join.

For more context on this Gospel episode, see Part I.

Parables of God’s Love for Sinners

The Preaching of the Cross, Vol. II

Chapter IX

St. Luke xv. 1—32 ; Story of the Gospels, § 124

Burns and Oates, 1886.

(Read at Holy Mass on the Third Sunday after Pentecost)

How Jesus responds to the charge of associating with sinners

The accusation you might miss in the Parable of the Lost Sheep

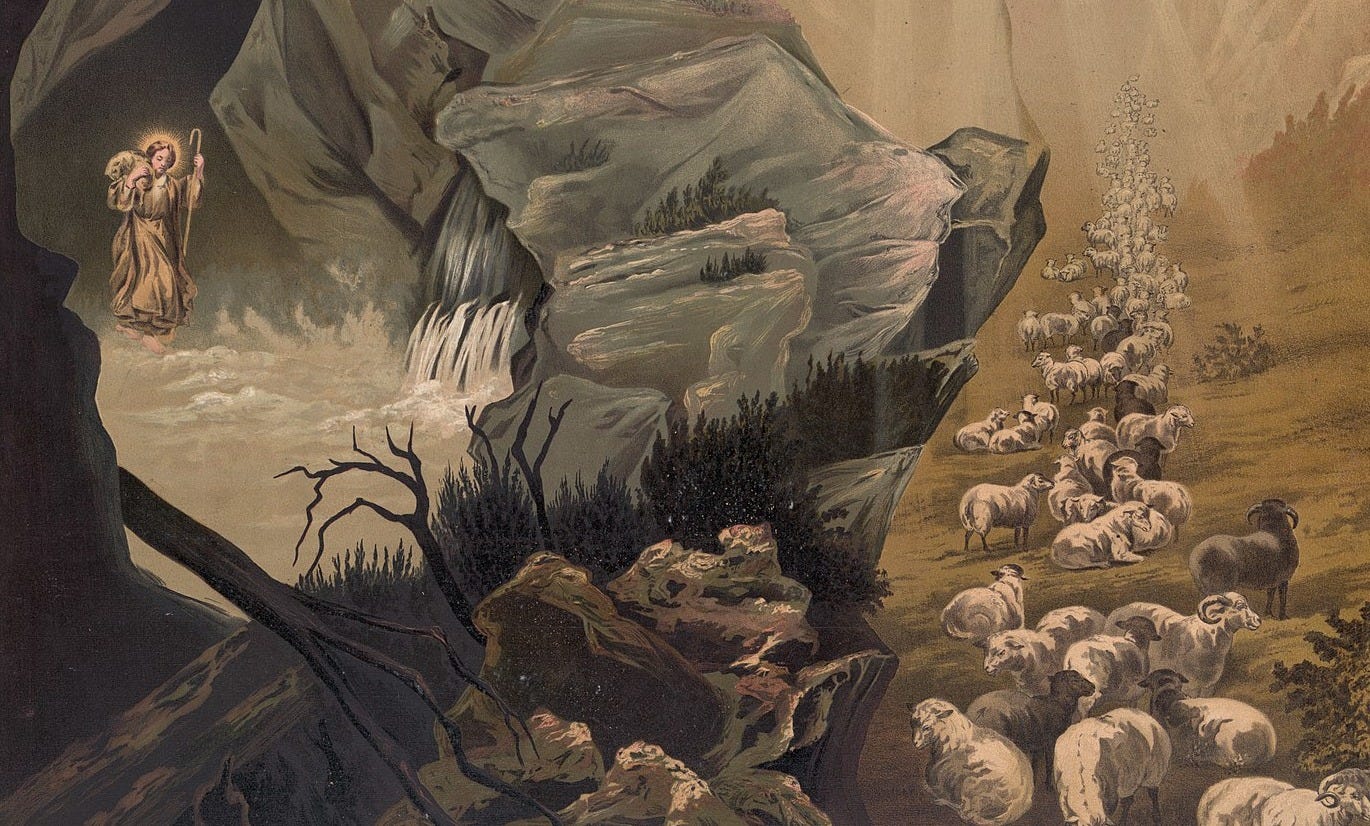

The Lost Sheep

‘And He spake to them this parable, saying, What man of you that hath a hundred sheep, and if he shall lose one of them, doth he not leave the ninety and nine in the desert, and go after that which was lost, until he find it? And when he hath found it, lay it upon his shoulders rejoicing, and coming home, call together his friends and neighbours, saying to them, Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep which was lost?

‘I say to you that even so there shall be joy in Heaven upon one sinner that doth penance, more than upon ninety-nine just who need not penance.’

The argument which our Lord here uses is of the same character with that of some of the answers about the Sabbath. He had reasoned, then, from the natural kindness with which men would take an ox or an ass on the Sabbath and lead it to water, or save an animal that had fallen into a pit, notwithstanding that the strict letter of the Law forbade all work on the Sabbath-day. And He had drawn a contrast, which enhanced the force of the argument saying, ‘How much better is a man than a sheep?’1

And when a little before this time He had healed the woman who had a spirit of infirmity, He had argued, after speaking of the watering of the ox or the ass, ‘ought not this daughter of Abraham, whom Satan hath bound, lo, these eighteen years, be loosed from this bond on the Sabbath-day?’ Here the contrast is not drawn out, but it is implied, and our Lord seems to vary the images which He uses for the purpose of setting forth various truths concerning the souls of sinners, which made them so valuable in the sight of God.

The image of the shepherd seeking the one lost sheep would naturally occur to our Lord in the pastoral country of Judæa, in which, as has often been said, His Ministry now lay. Thus it might have been used by Him, as in harmony with the habits and scenery of the place in which He found Himself, as that of the sower and the seed, or the wheat and the cockle, had been used in Galilee. And when He speaks of the ninety-nine as left in the ‘desert,’ His hearers would understand that the country thus spoken of was not a desert in the common sense. But it may fairly be thought that He had other and deeper reasons for the use of this image on this occasion.

Our Lord the Good Shepherd

We have already seen how lovingly He dwelt on this same image while at Jerusalem for the feast of Tabernacles. He had now for a long time kept the thought of the Passion deliberately before His mind, the mystery which He summed up in His words about the Good Shepherd giving His life for the sheep. While He was preaching in Judæa during these months of the last year of His Ministry, this may be said to have been the most common contemplation of the Sacred Heart.

It was also peculiarly appropriate to the work on which He was engaged, for at this time, more than ever, He seems to have been burning with pastoral zeal, straining every nerve for the application to soul after soul of the merits of His Precious Blood. His love grew in its manifestations as His time became shorter, and in His dealings with sinners at this period He may have said to have illustrated St. John’s words concerning Him, that having loved His own who were in the world, He loved them to the end.

The publicans and sinners, with whom He was now charged with letting Himself be too familiar, were in His eyes the lost sheep of His flock, for the recovery of whom He was preparing to lay down His Life. They were outcasts as well as lost sheep. The whole nation despised and, to some extent, socially excommunicated, the publicans, who represented to them taxation in its most odious form, as the tribute levied by a foreign government which they could not resist.

Ezechiel’s description of the shepherds

The Pharisees and priests looked down on those who belonged to the class of sinners. These men who despised them were the very men who ought to have sought them out, for they were, in fact, the shepherds of the people, now only using their authority to drive them away from the true Shepherd.

They were men who incurred the guilt of those shepherds who were so vehemently denounced by Ezechiel the prophet, as when he says,

‘You eat the milk and you clothed yourselves with the wool, and you killed that which was fat, but My flock you did not feed. The weak you have not strengthened, and that which was sick you have not healed, and that which was broken you have not bound up, and that which was driven away you have not brought again, neither have you sought that which was lost, but you have ruled over them with rigour and with a high hand, and My sheep are scattered because there was no shepherd, and they became the prey of all the beasts of the field, and were scattered.’

And still further the Prophet goes on, after denouncing the crimes of the shepherds, and their rejection, to prophesy in words which our Lord may well have had in His mind:

‘Thus saith the Lord God, Behold, I Myself will seek My sheep, and will visit them as the shepherd visiteth his flock in the day when he shall be in the midst of his sheep that were scattered, so I will visit My sheep, and will deliver them out of all the places where they have been scattered in the cloudy and dark day.’2

And now with regard to these lost sheep, that had taken place which is figured in the parable, for they had been lost, sought out, found, and brought home in triumph.

If He ate and drank with them, as He had done once at the feast of St. Matthew, and would do again soon in the house of Zaccheus, that was but a poor figure indeed of the manifestation of joy which took place in Heaven at their conversion. They might feast Him and entertain Him after their poor rough coarse fashion, but with hearts full of the sincere love of the true penitent. He would accept their hospitality, join in their festivities, hallow their banquets, such as they were. For His Heart was full of ecstatic joy, and in its expansiveness and love of sympathy, He would call on all Heaven to rejoice and give thanks with Him.

Our Lord’s Sacred Heart is so full of joy that He paints in a figure, in the circumstances of the parable, the details of His labours and His triumph. He speaks of the man who leaves ninety-nine out of a hundred sheep in the desert, to go in search of the one sheep that has strayed. He speaks of how he treats it when it has been found, not driving it before him or even leading it, but carrying it home on his own shoulders.

And then follow the other circumstances of his calling together his friends and neighbours and bidding them rejoice with him. No doubt, every detail of the picture has been chosen, not simply that we might have a representation, though in poor human colours, of the delight of the Sacred Heart, but because there is something in the carrying out of the great counsel of the Redemption in individual cases which corresponds to each of these details. It is needless to say that, although we may not be able to say with certainty that this principle as to the meaning of all details should be applied to the interpretation of every one of the parables, we might still consider it probable that it should be frequently so applied, when we remember the manner in which our Lord has Himself explained some few of the parables for us.

Economy of the Redemption present to our Lord

This once admitted, it is natural to think that our Lord had present in His Sacred Heart the whole economy of Redemption, even those parts of it which may not strictly belong to the conversion of an individual sinner.

Thus some of the Fathers interpret the feature of the leaving of the ninety and nine sheep in the desert, as if it had reference to what St. Paul says of our Lord, that He took not on Him the nature of angels, but He left the heavenly companies above in order to seek out the poor race of mankind. The great end and object of the Incarnation is the finding and recovering what was lost. This is the one sufficient answer to our Lord’s critics.

When the shepherd is said to place the newly-found sheep on his shoulders, instead of driving it home before him, or treating it in any way as if it were worthy of punishment, we not only see in the description the tenderness of our Lord to the returning sinner, but are also reminded of the truth that our Lord took our nature upon Himself to redeem us, of the Cross which He bore up the Hill of Calvary that He might suffer for us, and of our entire dependence on Him in the matter of salvation. These things may not belong directly to the particular point which is in view in the parable as addressed to the Pharisees. But they belong to the great system of truths concerning the redemption of man, that bringing home of the lost sheep which our Lord had before His mind, and they belong to the history of the execution of the counsel of God through our Lord.

So also in the calling together of his friends and kinsfolk to rejoice with him, we have not only a picture of the immense exultation of the Sacred Heart, which is not satisfied without communicating His joy to His friends, and having a repeated and reflected delight in their joy on His account. For we are also taught concerning the tender and intimate love to us which animates all the dwellers in the world beyond the grave, between whom and ourselves there is the closest union through our Lord, and whose interest in us for His sake, as well as for our own, is a participation of His.

There are none in Heaven or in Purgatory who are like ‘elder brothers’ to the sinner, none to whom his return is not a matter of the purest and deepest joy.

Parables of God’s Love for Sinners

How Jesus responds to the charge of associating with sinners

The indictment you might miss in the Parable of the Lost Sheep

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Twitter (The WM Review)

St. Matt. xii. 12.

Ezech. xxxiv. 3–5, 11, 12.

I love Father Coleridge's detailed and sensitive treatment of this parable. As someone who has felt myself lifted on the shoulders of the Good Shepherd and brought home, I recognize the true portrait of the tender Saviour in his words.

The shepherds who reject and abandon the lost sheep are so far from being like Him. Jesus is at various times disappointed, dismayed, and angry with them, but Father Coleridge brings out so beautifully that joy swells his Heart in the telling of this parable and it softens His rebuke, hoping to touch their hearts.