Why Jesus asks, 'What think you of Christ, whose Son is he?'

In posing a question about King David, Our Lord offered his enemies one last lifeline.

In posing a question about King David, Our Lord offered his enemies one last lifeline.

Editor’s Notes

This chapter continues on directly from the previous – for more context, see Part I of the previous chapter.

In this first part, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How Christ’s final question used Psalm 109 to reveal His Divine Sonship.

That even in silence, Christ continued to teach, offering truth to His enemies.

Why His last public teaching was a merciful call to deeper understanding.

He shows us that the question of David’s Son was Christ’s final appeal to the hearts of His foes.

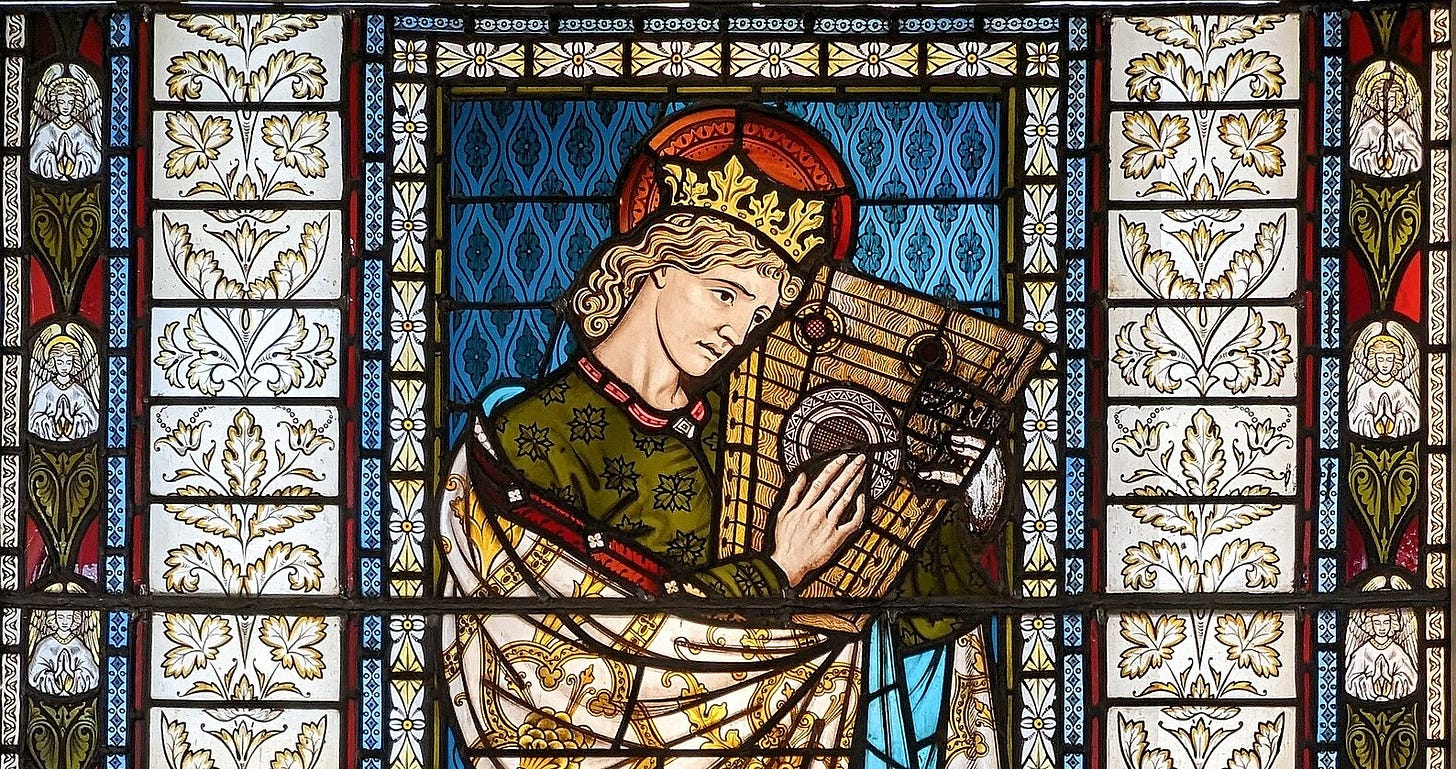

The Son of David

Passiontide, Part I

Chapter X

St. Matt. xxii. 34-40; St. Mark xii. 28-34

Story of the Gospels, § 140

Burns and Oates, London, 1887

Our Lord’s question

The Pharisees seem to have left the part of the Temple in which our Lord was teaching, after the answer which He had given to the question about paying tribute. They returned again after the question of the Sadducees, in whose comfutation they seem to have taken great pleasure. They were present, therefore, as it appears, at the question of the Great Commandment, and at the answer which one of their own body made to our Lord’s reply.

There was no open hostility, for the moment, in their behaviour towards Him, but the silence from all questioning, which they adopted from this moment, is noted by the Evangelists, as if it was something which surprised them and which they thought worth recording.

Then our Lord in His great mercy broke the silence Himself, putting before them a simple question, the right solution of which would apparently have led them on to higher things, and more true thoughts about Himself, and the duties incumbent upon them at the present crisis of their trial.

Silence of the Priests

‘And the Pharisees being gathered together, And Jesus answering said, teaching in the Temple, How do the scribes say, that Christ is the Son of David?’

St. Matthew puts the question as directly addressed to the Pharisees themselves:

‘What think you of Christ? Whose Son is He? They say to him, David’s. He saith to them, How then doth David in spirit call Him Lord, saying, The Lord said to my Lord, sit on My right hand, until I make Thy enemies Thy footstool? For David himself saith by the Holy Ghost, The Lord said to my Lord, sit on my right hand, until I make thy enemies thy footstool. David therefore himself calleth Him Lord, and whence is He his Son?’

The difference between the two accounts is easily explained, for our Lord was teaching the people, and put the question to them about the scribes, turning afterwards directly to them for the confirmation of His statement about them, and repeating the question to them before all. ‘And no man was able to answer Him a word, neither durst any man from that day forth ask Him any more questions.’

These questions of the Pharisees and Sadducees and others, seem to have been put to our Lord on the Tuesday in Holy Week, and it is often considered doubtful whether that was not the last day on which He taught in the Temple. But in any case it must either have been the last day or the last day but one—for it is not thought that He taught in the Temple on the Thursday, on the evening of which the Last Supper was celebrated.

The Evangelists may mean, therefore, to insist upon this silence of our Lord’s enemies as remarkable in itself, and the Wednesday may have been reserved by Him for His final denunciation of the Scribes and Pharisees before leaving the Temple altogether, which was followed by His sitting on the Mount of Olives over against the Temple, and delivering His prophecies concerning its destruction, the destruction of Jerusalem, and the end of the world. This denunciation of the Pharisees would thus be a teaching of our Lord apart from any other, and would have a special solemnity of its own.

This question of the Sonship of Christ to David seems to have been the very last of our Lord’s teachings, in the ordinary sense of the word, the last opportunity given to the Scribes and Pharisees of lifting themselves out of the darkness in which they lay.

Psalm 109

The passage quoted by our Lord is, as we all know, from Psalm cix., the Davidic origin of which has never been called in doubt by any reasonable critics, either among Jews or among Christians. In point of fact, our Lord Himself attributes the Psalm to David, and would not have used the quotation if there had been any question on the matter among the Jews of His time. Here again we must insist on our often repeated commentary, that our Lord, when He quotes Scripture, constantly means to direct the attention of His hearers, not only to the particular words which He cites, but also to the whole context of the passage from which the words are taken.

The Psalm here quoted is very short, and every verse of it is full of the deepest meaning and the most important doctrine. It is not strange, therefore, if we should suppose that He wished to bring before the minds, especially of the learned men among the audience, the doctrine of which the Psalm is full, and that therein was to be found the key to the difficulty of the Jews in receiving Him as He ought to have been received, as far as that difficulty came from a simple want of knowledge and intelligence of the Scriptures.

Certainly refers to Christ

Not only is the Psalm in question undoubtedly of David as its author, but with equal certainty it refers to Christ. No one questioned this fact at the time at which our Lord adduced it in the Temple, though it would have been obvious to an objector who could do so, with any appearance of truth, to say that David was not speaking of Christ, and that therefore the difficulty alleged by our Lord did not apply. St. Paul, writing to the Hebrew Church, uses the Psalm again, and he uses it of Christ, showing from its words the pre-eminence of Christ over the angels.

‘For to which of the angels said He at any time, Sit on My right hand, until I make Thy enemies Thy footstool?’

And at the opening of the same passage St. Paul says in the same way:

‘To which of the angels hath He said at any time, Thou art My Son, to-day have I begotten Thee?’1

The teaching of the Psalm may be divided into three heads, for it teaches, first, the Humanity of Christ, in which He is inferior to the Father, secondly, His Divinity, in which He is equal to the Father, and thirdly, His Priesthood after the order of Melchisedec, and therefore His mediatorial office, in which the redemption of the world was to be wrought out by Him, by His sacrifice of Himself on the Cross.

Doctrine of the Psalm

The Human Nature of Christ is shown in the first verse, where His exaltation to the right hand of God is spoken of, and this evidently implies that He is raised to a position to which human nature would have no right of itself. The exaltation of our Lord is constantly attributed to the Father, and the Psalm speaks of it in the first verses, ‘The Lord,’ that is, God the Father, ‘said unto my Lord, the Incarnate Son in His Human Nature, ‘Sit Thou on My right hand until I make Thy enemies Thy footstool.’

It is clear therefore that we have here the Humanity of Christ spoken of as exalted to the right hand of God, that is, raised to the throne of Divine glory. If the Eternal Son is capable of exaltation and of sitting on the right hand of the Father, it is in His Human Nature that that is true. The Psalm then speaks plainly of the power and dominion given to the Sacred Humanity and the triumphant extension of His Kingdom over the whole world.

‘The Lord shall send forth the rod of Thy power out of Sion, have Thou dominion in the midst of Thy enemies.’

It speaks also of His eternal generation in the following verse, although there is here apparently some difference between the Greek text and the Hebrew, which makes some obscurity. It then announces the Priesthood of the Eternal Son made Man, in words which are taken up again by-and-bye by St. Paul.

It must be noted also that the last verses of the Psalm speak of the effects of the redemption brought about by the sufferings and humiliations of the Meditator, Who is to judge among the nations, dividing the good from the bad, the saved from the lost, Who is also to fill up and repair by His Redeemed the ruined ranks of the angels, whose loss is to be supplied by the humble, and Who is to drink of the brook of humiliations in the way of this mortal life, and be Himself exalted because He so humbled Himself, and He is, to those who follow Him, the cause of their exaltation.

This is enough to give a short account of the great truths which are hinted at in this Psalm, and also to make it clear how aptly and how mercifully our Lord selected the question which He put to His enemies and to the people in general, before He proceeded to enter on His Passion.

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

The Son of David

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Heb. i. 5-12.

Thank you and very interesting......The Roman leaders , I understand, often adopted "sons" who were then to be put in leadership positions. Adopted as adults. Is this term "Son of David" framed in the same way, so that the learned ancients could understand better the humanity of Christ ,and His stature, even if they could not grasp the Divinity of Christ? Especially in light of His many miracles. Blessings!