What is the difference between prayer before and after the Cross?

After the Crucifixion, prayer in Christ’s Name drew power from his Sacrifice—filling the Apostles with unshakable joy.

After the Crucifixion, prayer in Christ’s Name drew power from his Sacrifice—filling the Apostles with unshakable joy.

Editor’s Notes

On the Fifth Sunday after Easter, the Church returns to John 16—which she had been reading on the Third Sunday. For more context on this passage, see here.

In this part, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How the Apostles would no longer need to ask Christ questions after Pentecost, due to the indwelling of truth.

That a new mode of prayer, in Christ’s Name and through his sacrifice, would then be fully established.

Why such prayer would bring fullness of joy: it draws its power from the accomplished Passion and the daily pleading of the Sacrifice.

He shows us that after Pentecost, Christian prayer would become inseparable from Christ’s mediatorship and the merits of the Cross, forming an unceasing offering before the throne of God.

For more context on this episode, see here.

Parting Words

Passiontide, Part III, Chapter VI

Chapter VI

St. John xvi. 16-33, Story of the Gospels, § 156

Burns and Oates, London, 1886

What is the difference between prayer before and after the Cross?

How does the power of the Apostles’ prayer continue in the Church?

How Christ’s plain words before the Cross reveal his love for the Apostles

Why Christ says ‘Have confidence, I have overcome the world’

‘In that day you shall not ask me anything’

‘In that day you shall not ask Me anything.’

The words are ambiguous in our language, in which the word to ask has the double signification of questioning and petitioning, and although the Greek word which is here used by St. John may sometimes be used in both senses, it appears from the context of the passage that it is to be taken in the sense of asking a question.

For the whole sentence is our Lord’s reply to a question which the Apostles wished to put to Him, on account of what He had said about the little time during which they were not to see Him, and the little time after which they were to see Him.

It is therefore more natural to suppose that these words mean that, in the time of which He is speaking, they shall not require to put questions to Him because they will be living in a new atmosphere, as it were, of truth clearly understood, that they will not need the perpetual answers from our Lord by which they had been accustomed to have their difficulties solved.

The new life after the coming of the Holy Ghost

The time of which our Lord speaks may be understood as including the time of the forty days after the Resurrection, but it seems clear that our Lord is referring to the new life which will be theirs after they have received the great gift of the Holy Ghost which is uppermost in His mind at this time. This was a new and greatly higher stage of spiritual enlightenment for them, though He conferred some portions of what they were then in possession of before the Ascension, as when He opened their understanding that they might understand the Scriptures.

Our Lord says that at the time of which He speaks they will not need, as we say, to have recourse to Him as of old. It seems clear that, as the conversation which He is now holding with them draws on to its close, He seems to speak more and more as if He had present in His mind that future condition of His Apostles which was to be their life after the Day of Pentecost, and which was to have about it so many new and more wonderful elements, making it in truth the enjoyment of a new creation, on account of the presence with them of the Divine Paraclete.

Uncertainty of our Lord’s meaning

Our Lord’s language here seems sometimes to leave it uncertain whether He is not speaking of a condition of things which cannot be perfectly realized till after this world has passed away, and they are already His companions in the possession of God. But there is nothing in these sentences which we can certainly apply to their state then.

Still, the language seems intended to hint to us the very great elevation of state on which they were to enter after the Day of Pentecost. Then He continues:

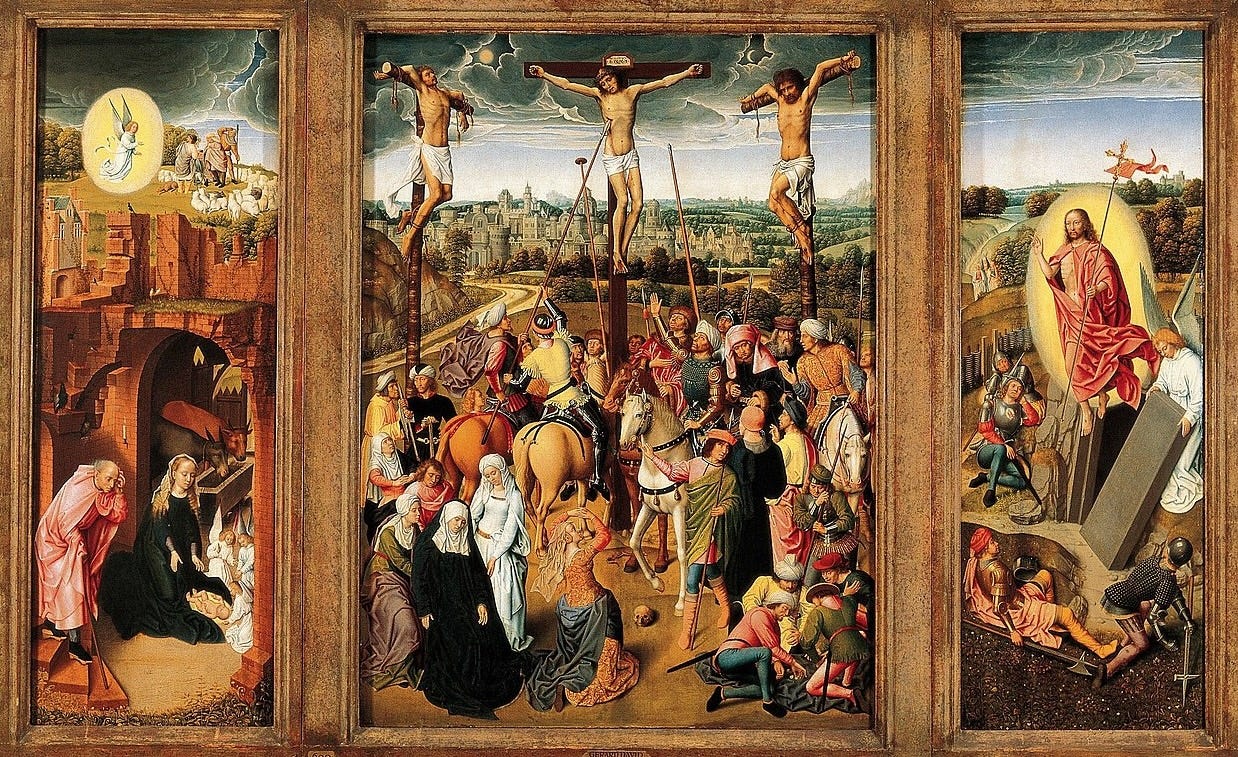

‘Amen, amen, I say to you, if you ask the Father anything in My Name, He will give it you. Hitherto you have not asked anything in My Name. Ask, and you shall receive, that your joy may be full.’

In this sentence our Lord uses the other Greek word, which is commonly used for prayer, and He tells them that whatever they ask the Father in His Name, which they do not seem as yet in the habit of doing, will certainly be granted them by the Father. He does not mean of course that the Father is not to be addressed in prayer, but that they are now to use the Name of Him, the Incarnate Son, in their petitions to God, asking through His merits, and in right of all that He has done for them, by making Himself their Mediator, conferring upon them the whole might of His mediation and sacrifice and intercession, which took effect, as it were, formally, from the Passion which He was now to undergo out of obedience to the Father, as the Saviour of the world.

The life of prayer new

It is clear that the difference must have been very great as regards the ordinary power of impetration, when the prayers were no longer made through a future sacrifice, and again when the sacrifice was to be pleaded as already accomplished, and the difference must have been still greater as to the confidence and hope with which the petitions were made in the several cases, and there was to be something new also, adding immense weight to the Christian prayer, when the prayer became so very much the pleading of the Adorable Sacrifice of the altar renewed day after day, and becoming, by the frequency with which that Sacrifice was offered in the Church, an almost unceasing stream of representation before the throne on high.

This, too, was one of the great novelties given to the Church after the Day of Pentecost, of which our Lord says necessarily so few words, which must not be left by Christian contemplation unhonoured. He wished this immense power now to become the ordinary instrument of their prayers, and the prayers of all Christians, which are thus to have a weight with the Eternal Father, which will be seen by His faithfulness in listening to the prayers thus made.

While our Lord was with them, and while the Passion was as yet unaccomplished, the merits of His Sacrifice were indeed applied in countless ways, and what He now enacts is that they should be always formally or virtually pleaded in Christian prayers of any sort, from the offering of the Adorable Sacrifice, which is the highest and most perfect pleading of the merits of the Cross, to the simplest aspiration of the devout heart which may be made in any place or at any time.

It seems more natural to understand the words before us of this kind of prayer, which could not be made in perfection without a full and intelligent faith in the truth and effects of the Sacrifice of the Cross for the salvation of the world, as accomplished by our Lord, and which therefore was in truth a thing of which even the Apostles might not have had a perfect intelligence until the Passion was completed, rather than of the more ordinary conditions of prayer, as that it must be made for things connected with salvation, and in a state of grace, and the like.

Ask and you shall receive

Our Lord tells them that hitherto they have not asked anything in His Name, which would under that other interpretation mean that they had never hitherto made their prayers to God with the perfect conditions of success. For He says:

‘Hitherto you have not asked anything in My Name. Ask, and you shall receive, that your joy may be full.’

The prayer is henceforth to be made in His Name, in the sense in which we now speak, and then they will receive what they ask to an extent and in a way which will fill them with joy. We are told of the seventy-two disciples, who were sent out to preach in the last year of our Lord’s Ministry, that they returned to Him with joy, saying that even the devils were subject to them in His Name. Then our Lord had told them that they were not to rejoice because the devils were subject to them, but rather because their own names were written in Heaven.1

In this place He had just said that after He had returned to them after the Resurrection they should have joy which no man could take away from them. His present words seem to promise something more than this, for their joy is to be made full, that is, complete, by their habitual exercise of successful prayer through His Name. He had said something like this when He had spoken of them as branches who abode in Him.

For in the sentence in which He contrasted such branches with those that did not abide in Him, and were to be cast forth and withered and gathered up and cast into the fire, He had said as a blessing opposed to this sad lot, that if they abode in Him and His words abode in them, ‘You shall ask whatsoever you will, and it shall be done to you.’2

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

Parting Words

What is the difference between prayer before and after the Cross?

How does the power of the Apostles’ prayer continue in the Church?

How Christ’s plain words before the Cross reveal his love for the Apostles

Why Christ says ‘Have confidence, I have overcome the world’

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

St. Luke x. 17-20.

St. John xv. 7.