How St Peter’s Pentecost sermon revealed the Church’s mission

The fire of Pentecost revealed the Church’s universal mission—foretold in prophecy, aided by Mary’s prayer.

The fire of Pentecost revealed the Church’s universal mission—foretold in prophecy, aided by Mary’s prayer.

Editor’s Notes

In this part, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How the miracle of Pentecost signified the Church’s universal mission to all nations through divine power.

That Mary, though silent, saw in this event the whole future of grace, preaching, and sanctity.

Why the presence of foreign Jews revealed God’s plan for the Church’s global expansion.

He shows us that Pentecost was the outward beginning of the Church, but in Mary’s heart its whole destiny was already known.

Mary at the Day of Pentecost

Mother of the Church: Mary in the First Apostolic Age

Book I, Chapter III

Burns and Oates, 1886.

How Pentecost confirmed Mary’s mission as Mother of the Church

How St Peter’s Pentecost sermon revealed the Church’s mission

Mary and Converts: How Our Lady shaped the first Christians after Pentecost

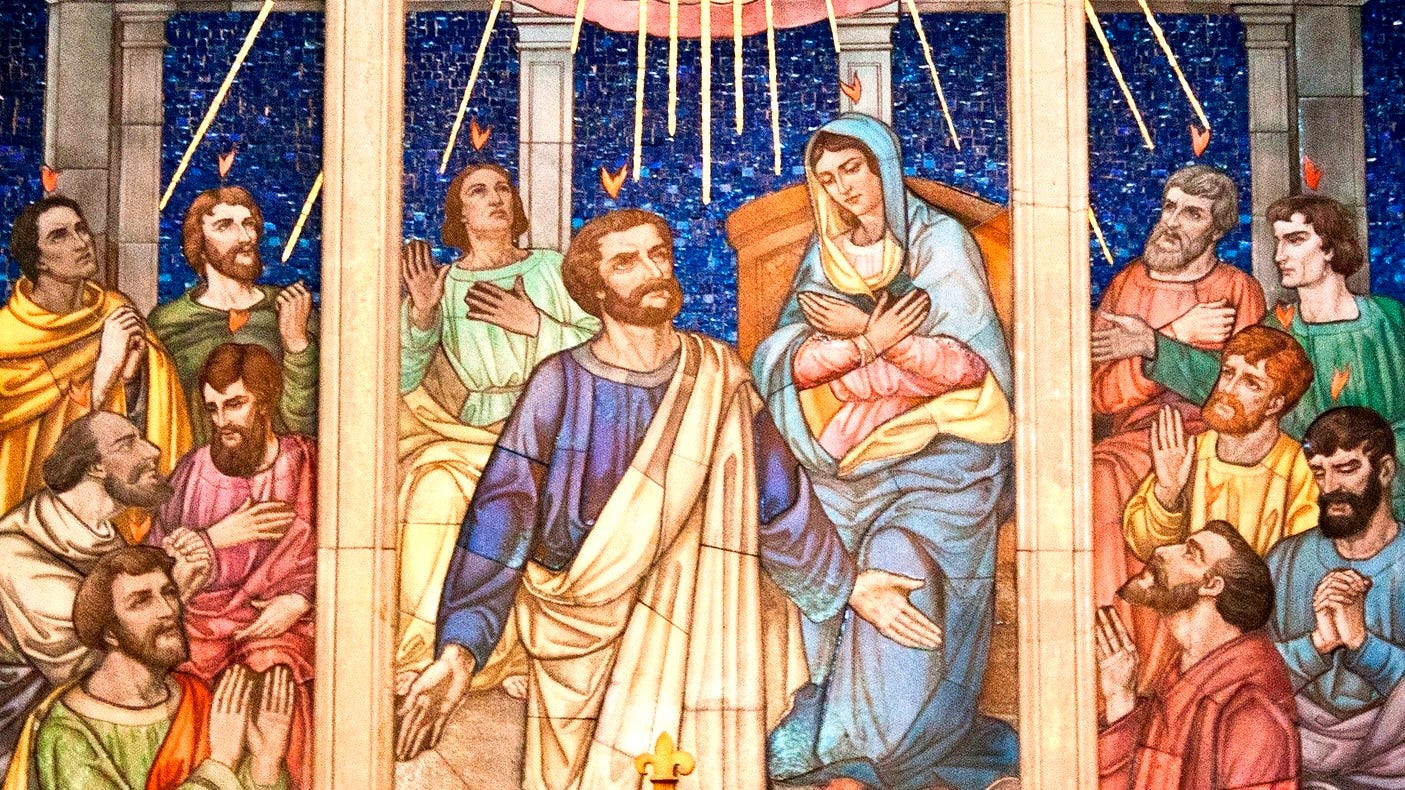

External incidents of Pentecost

The description of the external incidents of the Day of Pentecost belongs rather to the history of the Church as a body than to that of Mary. But her great part in the whole mystery can never be omitted, without making the history of the Church incomplete.

The first external incident seems to have been a great manifestation of the presence of the Holy Ghost in the kind of ecstatic delight and joy, passing from the soul to the body, which took possession of the whole collected body of the Apostles and disciples. They broke out into praises of God, thanksgivings, expressions of adoration, and the like, and in these it became evident that their thoughts and words were not their own, and that they were even speaking in new languages.

Their holy tranquil enthusiasm was something altogether unearthly, and they became scarcely masters of themselves in their joy, and in their expression of it. The noise of the wind, and perhaps other portents, seem to have drawn the multitude of which the history speaks to the neighbourhood of the Cenacle, where there must have been some open space capable of receiving so large a crowd.

It is clear that there must have been a reason for their collecting, and the fact that the disciples were talking in various tongues, or even had the fiery tongues visible over them, could not have become known of itself all over the city.

St Peter’s speech

When the multitude was collected, St. Peter made his speech, as St. Luke relates.

It is characteristic of this speech, as of others contained in this history, that there is no argument at all used to prove the truth of our Lord’s Resurrection except that of the witness of the Apostles, illustrated, indeed, by the prophecy of David in the Psalms. St. Peter explains that the marvels which his audience witnessed were but the fulfilment of other prophecies about the outpouring of the Holy Ghost.

But the pith, so to say, of his speech is contained in the words:

‘This Jesus hath God raised up again, whereof all we are witnesses. Being exalted therefore by the right hand of God, and having received of the Father the promise of the Holy Ghost’’—that is, the Holy Ghost Who had been promised—‘‘He hath poured forth this which you see and hear.’1

There is one circumstance in the scene which must have been providentially ordered for a special purpose.

The feast of Pentecost, like the other two great feasts of the Jewish calendar, would certainly always attract to Jerusalem a large number of Jews resident in foreign countries.

In this respect there would be no difference between the feast of Pentecost and the others. But it is certainly remarkable that on this occasion the crowd which was collected to hear the Apostles is said to have been made up in great measure of these foreign Jews, rather than of the inhabitants of Jerusalem or of the Holy Land.

When we think of the crowd which assembled outside the Praetorium at the Passion to force on Pilate the execution of our Lord, we think of them as Jews of Jerusalem and Palestine, rather than as foreigners. Here we have a crowd of foreigners, and St. Luke gives us a long list of the different parts of the world to which they belonged.

The miracle of the tongues would be unintelligible without this, and we must therefore consider it as a divinely ordained circumstance that so many of these foreigners should have met at the spot outside the Cenacle.

Miracle of the tongues

It appears probable that the miracle of the tongues was wrought in the way in which similar miracles have been from time to time wrought in the subsequent ages of the Church.

That is, the Apostles spoke in their own language, and the words fell on the ears of the hearers in the language to which they were accustomed. Otherwise, it is clear, there might possibly have been very great confusion, if one Apostle spoke one language for one set of foreigners, another for another, and so on.

There was also present a large body of Jews of Jerusalem and the Holy Land, as would seem from the exordium of St. Peter’s address.

Afterwards, when he speaks to the ‘men of Israel,’ it would seem that he included the foreigners. And at the end of the whole, when he exhorts them to receive Baptism, he says, ‘The promise is to you and to your children, and to all that are far off, whomsoever the Lord our God shall call,’2 words which seem to include the Gentiles as well as the Jews ‘‘of the dispersion.”

Thus at the very outset of the preaching of the Church, there was a foreshadowing of what St. Paul calls the mystery, ‘which in other generations was not known to the sons of men, as it is now revealed to His holy Apostles and prophets in the Spirit, that the Gentiles should be fellow-heirs, and of the same body, and co-partners of the promise in Jesus Christ by the Gospel.’3

The accomplishment of this mystery was to be, as we shall see, to the minds of the first faithful, a novelty of the most astounding character, and it is well to note in the earlier stages of the history the succession of hints and sayings by which their minds were prepared for the disclosure.

Our Lady’s prayer

Christian contemplatives will see in all these circumstances of the great outpouring of the Holy Ghost on the Church and her children, most abundant matter for the unceasing and most heavenly thanksgiving and prayer in which it was our Blessed Lady’s special office to occupy herself, on occasion of the great mysteries of salvation, as they succeeded one another in the Life of our Lord and in the subsequent history of His Kingdom.

No one could understand as she could the immensity of the boon which was conferred on the world, or see, as she could, the promise of the future glories of the Church in the marvellous incidents of that glorious morning.

The efficacy of the Apostles’ preaching, the blessing which attends the Word of God, the interior movements of the Holy Spirit in the hearts alike of preacher and hearers, the wonders of conversion, the grace of Baptism, the formation of the believers into one Body under the rule of the appointed ministers, the spread of these blessings into all the lands from which the multitude had been collected, and beyond them, over the whole world, the admission of all the nations among which these Jews were sojourners, and of the whole race of Adam, to the fruits of the Incarnation and Passion, all the heights of interior sanctity to which men were to be raised by the indwelling of the Holy Ghost, and the mighty achievements of the servants of God and the glories to which they would lead—all were calmly and devoutly counted over in the mind and heart of Mary.

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

Mary at the Day of Pentecost

How Pentecost confirmed Mary’s mission as Mother of the Church

How St Peter’s Pentecost sermon revealed the Church’s mission

Mary and Converts: How Our Lady shaped the first Christians after Pentecost

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Acts ii. 33.

Acts ii. 39

Ephes. iii. 5, 6.