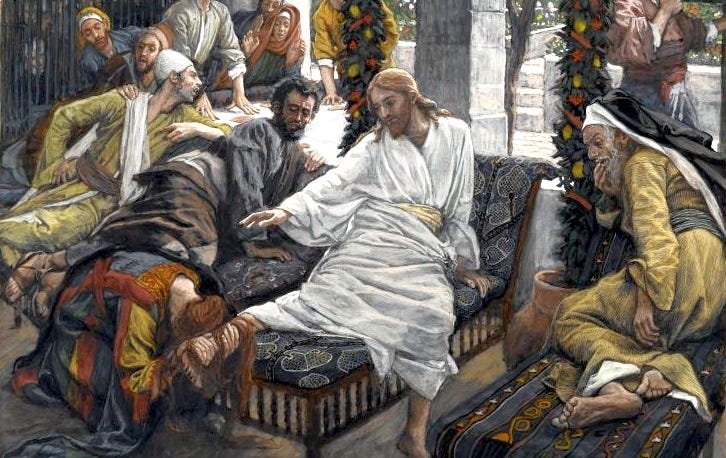

Did Mary Magdalene anoint Christ's feet?

Was she the same woman as Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus? And, given that there were two anointings, was she responsible for both, one, or none?

Was she the same woman as Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus? And, given that there were two anointings, was she responsible for both, one, or none?

Editor’s Notes

In this article, Fr. Coleridge discusses whether St Mary Magdalene is the same person as Mary of Bethany, and thus responsible for one (or both) of the anointings of Christ with costly perfume.

On the anointing of our Lord mentioned by St. Luke

Life of Our Life, Vol. I

Harmonistic Questions on § Story of the Gospels 55.

St. Luke vii. 36—50

The other anointings

The controversy which has been carried on as to the identity of this anointing of our Lord with that which is mentioned by the three other Evangelists as having taken place at the Supper at Bethany on the evening before Palm Sunday, need hardly be referred to here.

Nothing can show better the extreme lengths to which some writers may be led by the desire to make the Evangelists speak of the same occasions when they relate similar actions. All true principles of Harmony would have to be abandoned, if we were obliged to believe that the action and occasion spoken of here were the same action and the same occasion as those mentioned at so much later a period by St. Matthew, St Mark, and St. John.

The three, two or one persons

The distinction between the two unctions having been assumed, it remains to say a few words as to the person to whom the action is attributed in each case. Here there are three persons mentioned, or two, or one.

There is in the first instance the woman in the text of St. Luke, whom we may speak of as the sinner.

In the second place there is Mary Magdalene, who, under her full name, is not connected with either of the two unctions by any of the Evangelists.

Thirdly, there is Mary the sister of Lazarus, who is named by St. John in two places as having anointed our Lord.

The first place is in his eleventh chapter, where, when he introduces the history of Lazarus, he tells us that Mary his sister was the person who anointed our Lord and wiped His feet with her hair. This is before the second unction, which took place at the supper at Bethany. The second place is in his account of that supper, when he tells us, speaking of the family of Lazarus, that Mary took the pound of ointment and anointed, our Lord.

Thus, as far as these texts go—except for the feature in one of them of which we shall speak presently—we might suppose that the ‘sinner’ was the first to anoint our Lord, Mary the sister of Lazarus the second, and that Mary Magdalene had nothing to do with the unctions.

Or we may suppose, if we choose, that the ‘sinner’ and Mary the sister of Lazarus are the same person, but distinct from the Magdalene ; or again, that Magdalene is the ‘sinner,’ and Mary the sister of Lazarus another person; or again, that the ‘sinner’ and the sister of Lazarus and Mary Magdalene are the same person. This is the received tradition and opinion of the Church, although, as is only natural, there are to be found authorities and traditions which do not agree with this opinion.

Mary Magdalene as the ‘sinner’

The identity of the ‘sinner’ with Mary Magdalene seems to us almost too recognized a fact to be doubted, and it is confirmed by the statement made as to St. Mary Magdalene, both by St. Luke, in this place, and by St. Mark in his account of the Resurrection,1 that our Lord had cast seven devils out of her. She had therefore been a ‘possessed’ person, and it is quite likely that such a person would have been a sinner, though we are not told in what kind or measure her sins had been.

But this identification of the blessed Magdalene with the ‘sinner’ here mentioned is open to some plausible difficulties, and cannot be said to be directly proved by any passage in the Gospels. The identification of the sinner ‘with Mary the sister of Lazarus is far more easy. It rests, in the first place, on the direct statement of St. John, who, when he first mentions the sister of Lazarus, speaks of her as the person who anointed our Lord. As this passage of St. John refers to a time before the second unction, it is natural to understand that the Evangelist means us to understand him as saying that the Mary of whom he now speaks is the person who had anointed our Lord some time before, that is, at the first unction.

It may be added that no reason can be assigned for this statement of St. John’s, unless it be understood in this way. He was going to mention the second unction, and it would be altogether out of character with his usual manner to speak by anticipation of the person who was to perform it as having performed it. If he meant to identify Mary with the ‘sinner’ of St. Luke, the passage is intelligible.

Again, he would not have spoken of her as ή ἀλειψασα, if the action was still future, but as the person who ‘was to’ anoint our Lord, as he speaks of Judas as the Apostle who was to betray Him. In that place, (c. vi. 71), as in another (c. vii. 29), where St. John speaks of what was future at the time of the incidents of which he is writing, but past at the time when he wrote, he uses the auxiliary verb μἐλλειν instead of the aorist of the other verb. These reasons make it certainly difficult not to suppose that Mary the sister of Lazarus was the ‘sinner.’

The action is one which belongs, as it were, to one person, who might repeat it on an occasion like that of the supper, when she had so much fresh reason for love and gratitude towards our Lord, and when, moreover, she may well have had some foreboding of His approaching death. To imitate the action of another person would not be so natural, and to have done so would not have been enough to secure for the Mary of whom we are speaking the epithet which St. John gives her as ‘the Anointer of our Lord.’

The name ‘Magdalene’ never given

The only point, as has been said, at which the argument for the identification of the ‘sinner’ and the sister of Lazarus with St. Mary Magdalene fails to be absolutely demonstrative, is that the name Magdalene is never given to either in the passages in which either is certainly spoken of. At the same time, it may fairly be argued that this silence is easily explained, and, indeed, that the whole narrative taken together almost if not entirely supplies the absence of the identification by name.

The only Evangelist who names Mary the sister of Lazarus as the anointer at Bethany is St. John. If we are asked why he does not call her the Magdalene, and why, on the other hand, he uses the epithet Magdalene when he speaks of the women at the foot of the Cross and when he relates the history of the Resurrection, the answer is at hand. In these two places2 where he mentions Mary Magdalene, there are other Maries, either mentioned by himself, or present to his mind, from whom she was to be distinguished. It is not so in the narrative of the supper at Bethany. It seems to be St. John’s way to call her Mary, simply, when he can, and only to use the other name, Magdalene, when he is obliged for the sake of distinctness.

The burial of Christ

And in the second place, the history of the supper at Bethany itself is enough to identify Mary the sister of Lazarus with the Mary Magdalene of the Resurrection. For our Lord speaks of the anointing which was then performed as a part of His funeral rites, and bids the disciples let Mary keep what she has done for His burial. These words seem to imply that the Mary of whom our Lord spoke would certainly be foremost in the endeavours of the holy women His followers to anoint and embalm His Sacred Body, but that she would not be able then to do what she had done at Bethany.

It is almost impossible to suppose that this Mary would either have been absent at such a time, or that her presence would not have been noted. But nothing is said in the history of the Resurrection of Mary the sister of Lazarus, unless she be the same person as Mary Magdalene. If she is the same person, then our Lord’s words at the supper are easily understood, and the whole history of this devout lover of His becomes complete.

Reasons why St Luke might not have named her

A great many more arguments of a less direct kind have been adduced for this opinion, which is that which the Church follows in her offices for the feast of St. Mary Magdalene. We may further remove one possible cause of difficulty. St. Luke in the account of the sinner whose unction is the subject of his narrative, gives her no name. But almost immediately after this³ he speaks of a number of women who followed our Lord in His missionary circuit, and among these women he names Mary Magdalene. It seems strange that when he thus names her, he should make no reference to the scene which he has just described. The answer to this difficulty is twofold.

In the first place, it is fair to suppose that St. Luke would leave out the name of St. Mary Magdalene in the first scene out of respect to her, because he there speaks of a woman who was a well-known ‘sinner.’ But he would name her when he came to speak of the holy women who attended on our Lord.

In the second place, it is very probable that we have here an instance of the junction of two separate pieces in what we may call St. Luke’s collection. The fragment, so to speak, about the sinner belongs to one distinct section of the work, and the fragment about the holy women to another. And this may account for the absence in the text of any reference to the preceding anecdote.

Some objections are simply those of the pharisees

The other difficulties which have been raised against the identity of St. Mary Magdalene and the ‘sinner’ in this passage, from the alleged improbability that our Lord would allow such a person, as this woman is often supposed to have been, to minister to Him, and to go about after Him in the company of the holy women, need not be dwelt upon here. They are in the main only echoes of the speech of the Pharisee about her, as reported by St. Luke. At all events they will be best dealt with when the time comes for a full discussion of all that is here related concerning her.

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

St. Mark xvi. 9.

St. John xix. 25; xx. 1–18.