Effect of 'The Good Shepherd' on the different classes of the Jews

He was 'set for the fall and for the resurrection of many in Israel,' and this was beginning to take shape.

He was 'set for the fall and for the resurrection of many in Israel,' and this was beginning to take shape.

Editor’s Notes

In this part, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How the rulers' blindness and malice in the face of the Good Shepherd hardened, even as his miracles and mercy stirred many to believe.

That the faithful were forced to choose between Christ and their religious leaders, at the cost of exclusion.

Why the drama of these days foreshadowed not only the Passion, but the persecution of the Church.

He also explores the unnatural state in which Hebrew Christians found themselves, prior to 70 AD, in having to be opposed to their religious leaders.

For more on the context of this episode, see here.

The Good Shepherd

The Preaching of the Cross, Part I, Chapter XV

St. John x. 1–21.

Story of the Gospels, § 96

Burns and Oates, London, 1886

Why does Christ call the Chief Priests 'thieves and robbers'?

Why Christ is 'the door' through which every good shepherd must come

Why did the Good Shepherd tell the wolves they had no power over his life?

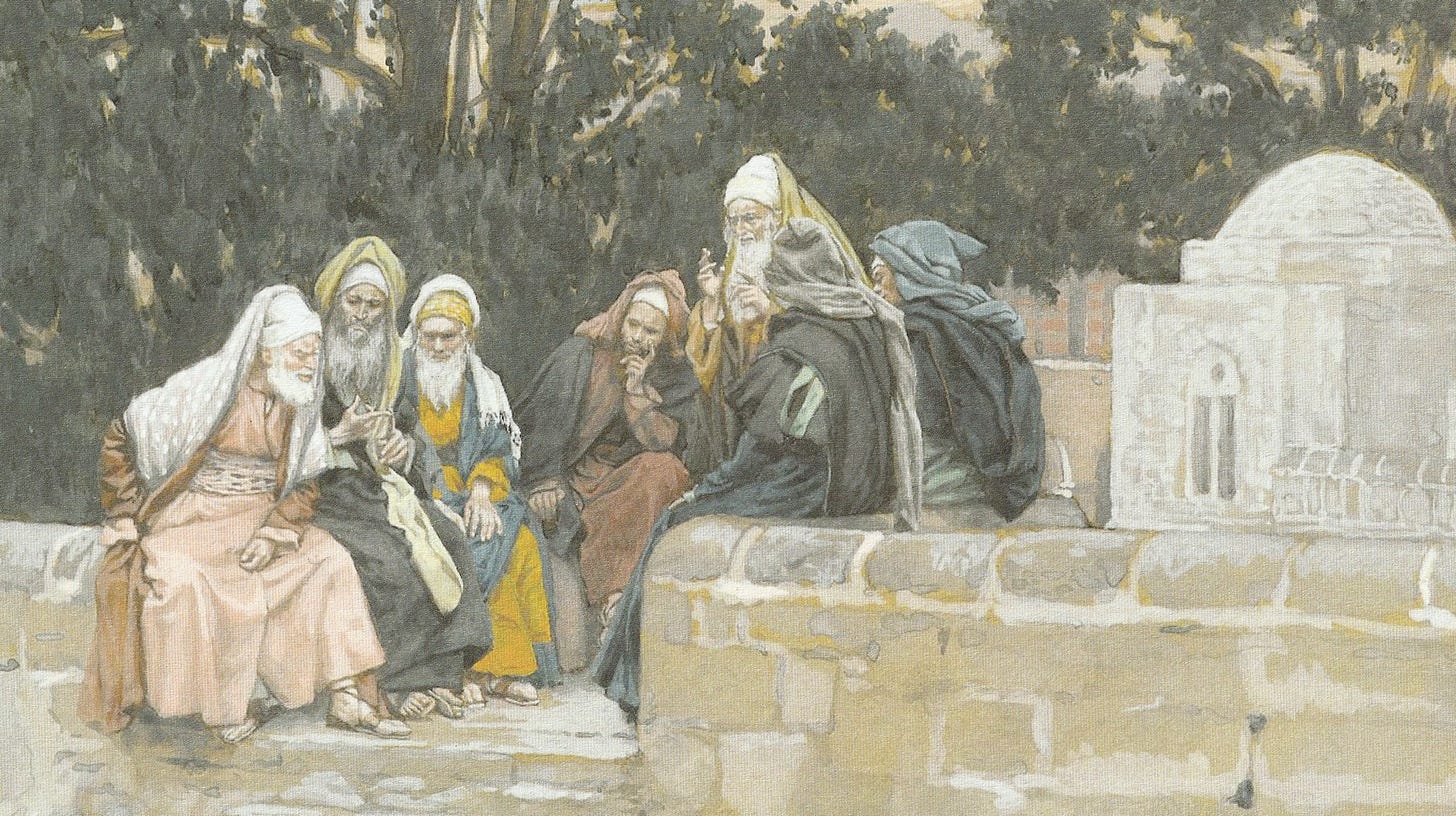

Effect of 'The Good Shepherd' on the different classes of the Jews

Influence of the incidents at the Feast

It is impossible to suppose that the incidents of the few days of which St. John has here supplied the history can have had but a slight influence on the public mind in general.

Our Lord’s name was already in the mouths of the people all over the Holy Land. The persons assembled at any of the great feasts must always have included a large number of strangers, that is, of Jews from different parts of the world. Thus these incidents, which passed chiefly in the Temple, the centre of attraction to the Jews both of Palestine and from other parts, must have taken place under the eyes of thousands, and the occasion on which they were assembled in the Holy City would make the discussion of religious questions a favourite occupation.

If our Lord’s name had been well known before, He must have become still more generally a subject of interest after this feast.

The Chief Priests

We have already spoken enough of the attitude of the Chief Priests, who are usually spoken of as the Pharisees and Scribes in the Gospels. Everything that had happened had hardened them more and more against our Lord. We know that the High Priest himself was now no other than Caiphas, a man evidently of bold, ambitious, and unscrupulous character, a man who in other days might have been known as an adroit politician, a man of keen insight in public affairs, and full of ready expedients in carrying out his own views.

The behaviour of Caiphas, a little later than this, when after the great miracle of the raising of Lazarus the enemies of our Lord met in council and determined to bring about His death, seems to show that either his office or his character, or perhaps both together, made him so influential as to be able to carry with him the greater number of the Chief Priests, even when what he proposed was in itself wicked and atrocious.

But it is the witness of history that there are usually, in such a collection of men in power, many who are unwillingly swept on by the strong and bold policy of their leaders, and who do not in their hearts approve all the measures in which they yet bear a silent part. It is probable that not all the Chief Priests were as wicked as Caiphas. Probably the division of the men of that rank, into the two sects of Pharisees and Sadducees, made it more difficult for those Pharisees who were inclined to hold back to disengage themselves from the necessity of following their own leaders, while the opposite party might be afraid of incurring the reproach of seeming to favour our Lord.

Secret disciples of our Lord

Moreover, as we can see in the cases of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, He had many secret adherents even among the ruling class. We do not know anything at this time about the attitude of Gamaliel, who afterwards rendered an important service to the Church in persuading the Sanhedrin to leave the Apostles to themselves,1 who was the master of St. Paul and St. Stephen and a number of others, and who ultimately became a Christian and a saint.

He may have been among those of whom our Lord might have said, as He did to the lawyer who questioned Him about the great commandment, that they were not far from the Kingdom of God. At least we can hardly think that such men shared the violent counsels and bitter obduracy of Caiphas.

Joseph of Arimathea is called by the Evangelists a disciple of Jesus, and ‘one looking for the Kingdom of God,’ though St. John adds that he was a disciple secretly, for fear of the Jews. There were others, perhaps, less advanced, who were ready to believe, but not yet disciples. Such were those of whom St. John speaks when he says that ‘many of the chief men also believed in Him, but because of the Pharisees they did not confess Him, that they might not be cast out of the synagogue, for they loved the glory of men, more than the glory of God.’2

And to these must probably be added a great many more, who were on the road to faith and conversion, and were even more likely than the others to be for the time intimidated by the tyrannical measures of their rulers. As far as we know, no voice was actually lifted up in our Lord’s defence, except that of Nicodemus on the occasion of which we have lately heard.

Perplexity of the people

No words can paint more truly the perplexed state of the popular mind, as distinguished from the rulers, than those which St. John reports in the case of the man who had been born blind, and to whom our Lord had given sight. The miracle wrought upon him by our Lord proved to him that He was a prophet.

‘What sayest thou of Him that hath opened thy eyes?’

‘He said, He is a prophet.’

This was the natural and reasonable effect of the miracles on the mind of the people. It may well be that they were powerfully drawn to believe in our Lord by His teaching also, for, as the officers said to the Pharisees, ‘Never did man speak like this Man’—whether the words referred to the beauty and sublimity of the doctrine, or to the authority with which it was set forth.

There were therefore more arguments than one, on the strength of which the people were ready to listen to our Lord, but it is natural to think that to them the miracles were the most cogent. Then, on the other hand, they were met by the declaration of their ecclesiastical rulers, as expressed in those words found in the same account, ‘We know that this Man is a sinner.’ The word of the authorities, as has been said more than once, weighed much with the people. But it was not enough to explain the miracles.

‘If He be a sinner, I know not, one thing I know, whereas I was blind, now I see.’

Nothing could obviate the plain fact of these miraculous cures, all of them most tender works of mercy as well as most marvellous displays of Divine power. The adversaries of our Lord were obliged to find some excuse for not giving in their own adhesion, in the face of evidence so strong, and thus we find them saying to the blind man, ‘We know that God spoke to Moses, but as to this Man, we know not from whence He is.’

The blind man’s argument

But the simple honest man at once put his finger on the weak point in their position. They were the teachers of Israel, they sat in the Chair of Moses, the people were bound to listen to them. But it was very strange, in a system that came from God, that, on the one hand, people should be bound to take their word, and that, on the other hand, they should be unable to answer the questions of the people.

‘Why, herein is a wonderful thing, that you know not from whence He is, and He hath opened my eyes. Now we know that God doth not hear sinners, but if a man be a server of God, and doth His will, him He heareth.’

They were more logical, though more desperately wicked, in their insinuation, made many months before in Galilee, and, as we shall see, soon to be repeated in Judaea, that He was in league with Satan, and cast out devils through the prince of the devils. There was no room for this insinuation here, and if it had been made it would have been rejected, as we see at the close of the narrative on which we have been dwelling.

The ecclesiastical rulers had adopted the same policy of giving no explanation of the wonderful facts before them in the case of St. John Baptist, as we see by their answer to our Lord when He asks them whether St. John’s baptism was from Heaven or of men. An authority which claimed allegiance was bound to see and to speak clearly. The people were ready with their own conclusion, which this man also expresses:

‘We know that God doth not hear sinners, but if a man be a server of God, and doth His will, him He heareth. From the beginning of the world it hath not been heard, that any man hath opened the eyes of one born blind. Unless this Man were of God, He could not do anything.’

Unnatural stain on consciences

It was thus, by the action of the authorities themselves, that the good and simple people who were brought into immediate contact with our Lord in His miracles or in His teaching, were driven to a kind of revolt against the constituted authorities of the holy nation. It was thus that all who, whether before or after the Passion and Resurrection, openly joined Him or the Church after Him, had to expose themselves to the risk of excommunication and persecution in the name of God Who had sent Him.

The Providence of God did not allow this strained and unnatural state of things to remain long. For, in the course of a single generation from the Day of Pentecost, Jerusalem was destroyed, the Temple, with all its sacred rites and associations, was swept away, the line of High Priests ceased, with all the hierarchy depending on them, the nation itself remaining as a witness to the world of God’s judgments, but remaining only as a proverb and by-word and warning.

But in the acts of these few days of the feast of Tabernacles, we can already see the germ, not only of the Passion, as brought about by the Chief Priests, but of the persecution of the Church of Jerusalem, of the savage outbreak which cost St. Stephen his life, and of the perpetual hostility under which the Christians of the Holy Land had so long to suffer.

Our present business is with the condition of the people of Judaea, to whom our Lord was now about to preach, as He had before done to the population of Galilee. We learn from what has been said the difficulties with which our Lord had now to cope, difficulties far greater than any which had confronted Him in His Galilaean preaching. We learn also to understand how it was that not to those who were to be Apostles alone it was well that He should set forth in all its fulness the doctrine of the Cross.

Those who were to become His disciples had now, indeed, to count the cost.

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

The Good Shepherd

Why does Christ call the Chief Priests 'thieves and robbers'?

Why Christ is 'the door' through which every good shepherd must come

Why did the Good Shepherd tell the wolves they had no power over his life?

Effect of 'The Good Shepherd' on the different classes of the Jews

Read Next:

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Acts v. 34, 39.

St. John xii. 42, 43.