The fate of Judas after his treachery

Judas seems to have wandered alone with a deluded conscience, until the sight of Christ condemned shattered all his illusions: he was a traitor, guilty of innocent blood.

Judas seems to have wandered alone with a deluded conscience, until the sight of Christ condemned shattered all his illusions: he was a traitor, guilty of innocent blood.

Editor’s Notes

In this part, Fr Coleridge tells us…

How St Matthew shows Judas’ end as both personal collapse and prophetic fulfilment.

That false repentance without hope or love leads not to salvation, but to despair and death.

Why the allusion to Achitophel reveals Judas as the antitype of David’s traitor, foretold in the psalms.

He shows us that remorse without trust in Christ becomes a noose rather than a remedy.

Treachery in Tradition

St Paul mentions traitors in his letter to St Timothy:

Know also this, that in the last days shall come dangerous times.

Men shall be lovers of themselves, covetous, haughty, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, ungrateful, wicked, without affection, without peace, slanderers, incontinent, unmerciful, without kindness, traitors, stubborn, puffed up, and lovers of pleasure more than of God: having an appearance indeed of godliness but denying the power thereof.

Now these avoid.

For of these sort are they who creep into houses and lead captive silly women laden with sins, who are led away with divers desires: ever learning, and never attaining to the knowledge of the truth. (1 Tim. 3.1-7)

In addition, the propers of Maundy Thursday give a truly harrowing impression of Judas’ fate—especially when we consider how these phrases are sung again and again, particularly repeating on five occasions that it would have been better for Judas if he had never been born.

Resp. IV: The sign by which my friend betrayed me was a kiss: whom I shall kiss, that is he: hold him fast: he that committed murder by a kiss gave this wicked sign. * The unhappy wretch returned the price of blood, and in the end hanged himself.

V. It had been good for that man, if he had never been born.

The unhappy wretch the price of blood, and in the end hanged himself.

Resp. V: The wicked merchant Judas sought our Lord with a kiss. He like an innocent lamb refused not the kiss of Judas. * For a few pence he delivered Christ to the Jews

V. It had been better for him if he had never been born.

For a few pence he delivered Christ to the Jews.

Resp. VI: One of my disciples will this day betray me: woe to him by whom I am betrayed: * It had been better for him if he had never been born.

V. He that dips his hand with me in the dish, is the man that will deliver me into the hands of sinners.

It had been better for him if he had never been born.

One of my disciples will this day betray me: woe to him by whom I am betrayed: * It had been better for him if he had never been born.

Resp. VIII: Could ye not watch one hour with me, ye that were eager to die for me? * Or do you not see Judas, how he sleeps not, but makes haste to betray me to the Jews?

V. Why do ye sleep? Arise and pray, lest ye fall into temptation.

Or do you not see Judas, how he sleeps not, but makes haste to betray me to the Jews?

With that in mind, let us cultivate the virtue of loyalty and integrity, and keep before ourselves the words attributed to St Philip Neri:

O Jesus, watch over me always, especially today, or I shall betray you like Judas.

Caiphas

The Passage of Our Lord to the Father

Chapter VII

St. Matt. xxvi. 59-75, xxvii. 1-10; St. Mark xiv. 55-66, 72; St. Luke xxii. 55-71, xxiii. 1; St. John xviii. 17-8, 25-27.

Story of the Gospels, § 162-4

Burns and Oates, London, 1892

History of Judas

It is here [after the trial before Caiphas] that St. Matthew inserts the account, which he alone gives, of the miserable end of the poor traitor, Judas.

We cannot feel certain that it was just at this point of the history of the Passion that what he here records took place, for he is usually guided by the order of thought rather than the strict order of time, and there can be no harm in following him on this occasion, as it seems a natural sequel to what has gone before.

We have no means of tracing the steps of Judas since the moment of his kiss of betrayal. The armed men who had it in charge to seize our Lord, after the signal had been given them by the poor traitor, had probably enough to occupy them in making their prey secure, and the other group of the Apostles and friends of our Lord would naturally disperse.

Judas would find himself nearly alone, with no one to watch him or to keep him company—at least he would be no object of interest to any one, as soon as his covenanted part had been discharged. The captors of our Lord would shun him almost as readily as his former companions. Probably he had no friends in the city, having been so long one of the little community which had gathered round our Lord.

Many conjectures and theories have been hazarded as to a mixture of motives in him, which may have led him to his crime without realizing the full consequences to which it was to lead, by writers who have supposed that he expected nothing more than another failure on the part of our Lord’s enemies to obtain possession of His Person. All these are merely the imaginations of the minds of those who have formed these theories, for the Evangelists tell us absolutely nothing.

His loneliness

Judas, left to himself, and having obtained, as we suppose, the covenanted pieces of silver for which he had sold our Lord, may have wandered friendless and with no companion but his own unhappy conscience, perhaps unable to tear himself away from the neighbourhood of the place in which the evil which he had set on foot was to be carried out by others to its full issue.

Thus after many hours of troubled wandering, he may have been in the streets of the city among the crowd which gathered in the early morning, and which may have been drawn together by the unwonted sight of the large procession of the Chief Priests and Scribes who accompanied our Lord in order to deliver Him formally into the keeping of the Roman Governor.

The Evangelist speaks of Judas as seeing that He was condemned, and the words admit of, though they do not require of necessity, the explanation that Judas gathered the fact that the sentence of condemnation had been passed from the appearance of our Lord in chains in the midst of His accusers, who were taking Him in triumph to the authority who alone had the power to sentence Him to death.

The sight may have been to Judas the assuring proof that the full aim of our Lord’s enemies had been attained, and thus may have put an end to all doubt in his mind as to the issue of his own treason. The evil conscience which had been haunting him so long with anticipations of the possible results of his crime, suddenly became an overwhelming sense of the irretrievable harm which he had brought upon his Master, and there was no hope left that anything might occur to avert the ruin of which he had been the chief instrument.

His first thought seems to have been how he could free himself from the responsibility of what he had done, and for this he could see no way better than to give back the money he had received as the wage of his crime.

St Matthew’s account of his suicide

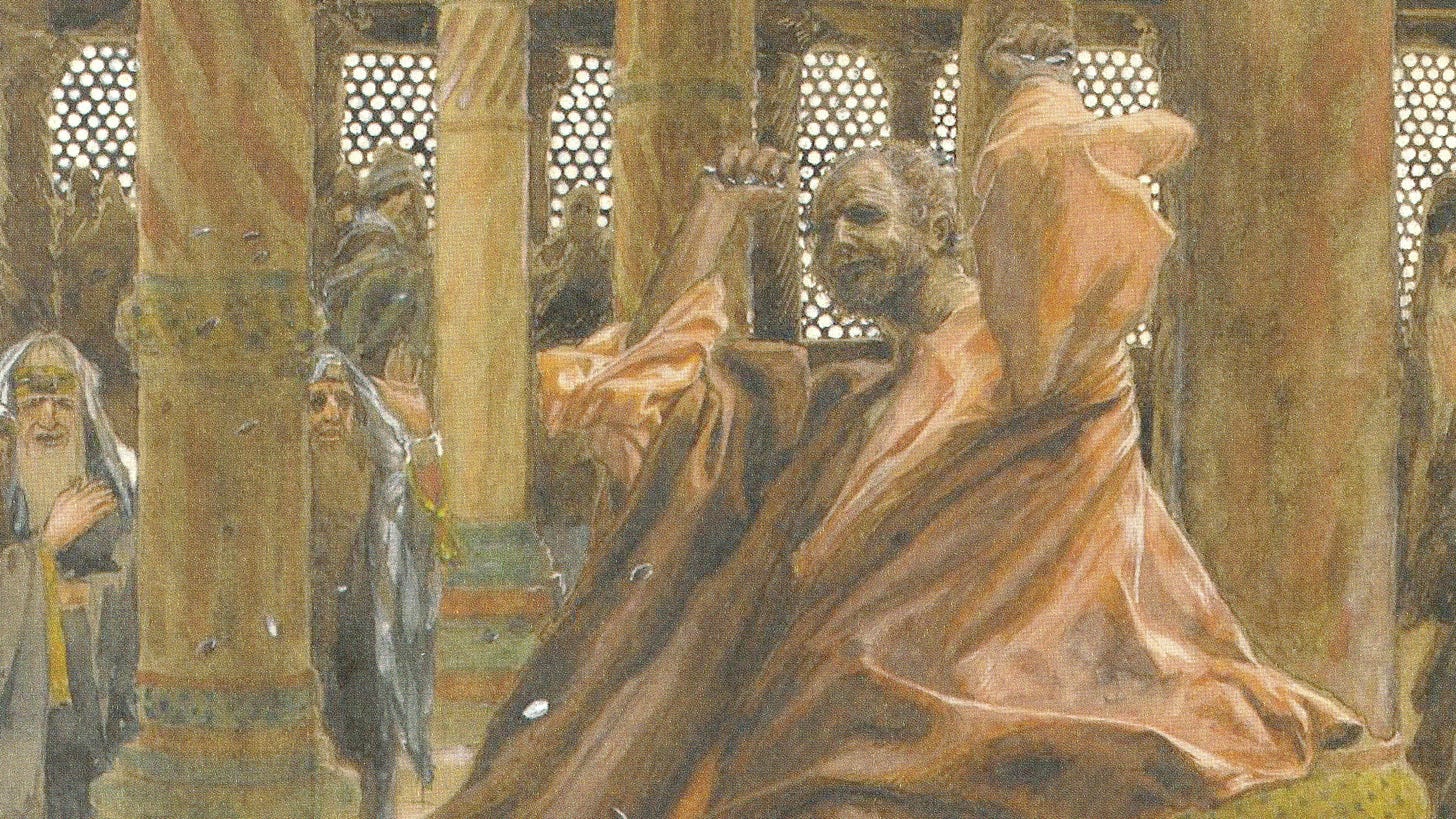

‘Then Judas, who betrayed Him, seeing that He was condemned, repenting himself, brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the Chief Priests and the ancients, saying, I have sinned in betraying innocent blood. But they said, What is that to us? look thou to it. And casting down the pieces of silver in the Temple, he departed and went and hanged himself with a halter.’

St. Matthew is here following his rule of noticing, when he has the occasion, whatever hardly observed fulfilments of prophecy can be pointed out in the history of our Lord. The Greek words which we translate ‘went and hanged himself with a halter,’ are taken from the Septuagint version, where they occur in the account of the suicide of Achitophel, the false friend of David, who went away when his counsel was not taken by Absalom.

The use of the words here open to us the whole picture of the parallel between Achitophel and Judas, which is frequently brought to mind in the psalms which relate to the Passion. It is as if St. Matthew had said of Judas that he killed himself as Achitophel did.

It seems very likely that the Evangelist of whom we are speaking was led to insert his account of the ‘penitence’ of Judas to some extent out of his wish to preserve the fulfilment of prophecy which we have just now pointed out. It is remarkable that he adds to it another instance in which he has noted another case of the same kind of anticipation of what occurred at this time, in the purchase of the potter’s field of which mention is made in the prophetic books of Zacharias and Jeremias.

‘But the Chief Priests, having taken the pieces of silver, said, It is not lawful to put them into the corbona—the sacred treasury—because it is the price of blood. And having taken counsel together, they bought with them the potter’s field, to be a burying-place for strangers. Wherefore that field was called Haceldama, that is, the field of blood, even to this day. Then was fulfilled that which was spoke by Jeremias the Prophet, saying, And they took the thirty pieces of silver, the price of Him that was valued, Whom they prized of the children of Israel, and they gave them unto the potter’s field, as the Lord appointed to me.’

It is clear that to the mind of St. Matthew the whole of the Sacred History was ever full of anticipations, more or less clear, of what was to take place with regard to our Lord, and that he and others fastened on them most eagerly.

We all know the chief difference between Judas and St Peter—but have we ever thought about the different effects they each had on Our Lord in his Passion?

Find out in Part II. Subscribe now to never miss an article:

Caiphas

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram: