Cursing the fig tree: Jesus' strangest miracle?

Why did Christ curse the fig tree if it wasn’t even fig season?

Why did Christ curse the fig tree if it wasn’t even fig season?

Editor’s Notes

On the 9th Sunday after Pentecost, the Church reads the account of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, at the start of Holy Week.

In particular, we hear of Our Lord weeping over Jerusalem, prophesying its doom, and his second cleansing of the Temple – the first having taken place much earlier in his public life.

St Luke’s account suggests that the Temple was cleansed immediately upon Our Lord’s arrival. However, St Mark’s account makes clear that it occurs on the following day – Our Lord having retreated to Bethany for the evening.

The fig tree

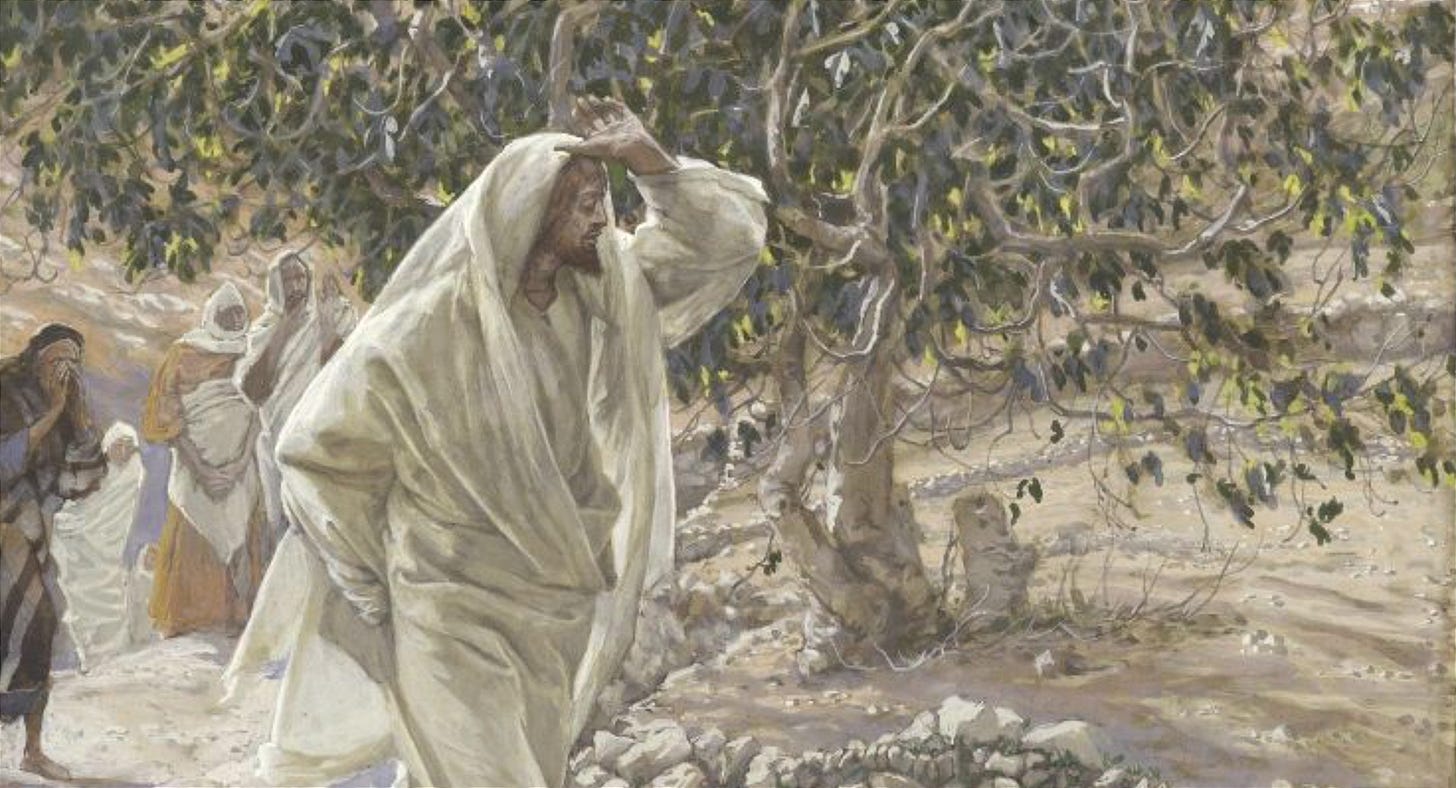

On his way back to Jerusalem, Our Lord approaches a fig tree to search for fruit. When he finds none, he curses the tree never to bear fruit again. The apostles later find the tree to have withered away.

This may appear to be a very strange miracle. Coleridge points out that it is one of only two “destructive” miracles – the other being the casting out of the Legion of demons into a herd of swine, who throw themselves from a cliff. But even in that latter case, it was not Our Lord who directly destroyed the swine – whereas here, he directly curses the tree.

Coleridge explains that this miracle was also a parable, and places this in the context of several other incidents, including:

Our Lord’s parable of the unfruitful fig tree, given three years to bear fruit

Our Lord’s cleansing of the Temple

The controversy with the Pharisees and Priests at the start of Holy Week.

The coming destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD

His parable of the eventual fruitfulness of the fig-tree at the end of the world

This context sheds considerable light on this confusing event – as well as revealing Christ’s righteous judgment against fruitless and hypocritical religion.

However, Our Lord’s subsequent references to prayer and faith might seem to undermine such an explanation – but Coleridge explains precisely why Our Lord refers to these important truths, rather than the more disturbing realities revealed in the cursing of the fig tree.

The Barren Fig-Tree

Passiontide, Part I, Chapter III

St. Matt. xxi. 19–22; St. Mark xi. 13–26; St. Luke xix. 45–48.

Story of the Gospels, § 134

Burns and Oates, London, 1889

Headings and some line breaks added.

Date of the incident

If we were to follow St. Matthew implicitly in the order in which he has arranged the events of these first days of Holy Week, we might be inclined to suppose that the cleansing of the Temple, which took place at this time, happened on the same day with the Procession of Palms. The mistaken impression which St. Matthew’s order might occasion, without any meaning on the part of the Evangelist, is at once corrected by the account of St. Mark, who tells us that the Day of Palms closed, as we have described it in the last chapter. We have given St. Mark’s words about the doings of the Day of Palms.

‘And He entered into Jerusalem, into the Temple, and having viewed all things round about, when now the eventide was come, He went out to Bethania with the Twelve.’

The Greek speaks more precisely, implying that it was already late when He was in the Temple. The expression, having viewed all things round about, certainly excludes the supposition that He then purged the Temple. St. Mark adds that He returned to the Temple, as it seems, early in the morning. On His way to Jerusalem occurred the significant incident of the unfruitful fig-tree, the withering up of which, at the word of our Lord, was noticed by the Apostles as they accompanied Him to Jerusalem on the following morning, that is, on the day after He had cursed it. The same day with the cursing of the fig-tree is also assigned to the casting out of the buyers and sellers from the Temple, as has been already said.

Miracle on the fig-tree

‘And in the morning, returning into the city, He was hungry, the next day, when they came out from Bethania, He was hungry. And when He had seen a fig-tree far off, having leaves, He came, if perhaps He might find anything on it.

‘And when He was come to it, He found nothing but leaves, for it was not the time for figs, and answering, He said to it, May no man hereafter eat fruit of thee any more for ever, May no fruit grow on thee henceforth forward for ever. And immediately the fig-tree withered away.

‘And the disciples seeing it, wondered, saying, How is it presently withered away? And His disciples heard it.’

We have combined the two narratives of the Evangelists, and from them it seems clear that the fig-tree, perhaps, withered away immediately, but that the notice of its withering, as taken by the disciples, must be placed on the subsequent morning, when they again passed by the spot. There is, however, no improbability in the supposition that they observed it both when it withered up and at the time when they next passed it and spoke of it.

Meaning of the action

This miracle on the fig-tree is noted among the works of our Lord, as having been almost the only instance in which He exerted His miraculous power for destruction and not for blessing. The only other instance of the same kind that can be alleged is the permission which He granted to the legion of demons to enter into the herd of swine, which they immediately forced to plunge themselves in the lake. But that was in truth a miracle of mercy, for it was the sequel to His casting the devils out of the possessed man.

In the present case, it seems clear that the miracle was a parable as well as a miracle, and that the miracle was wrought for the sake of the parable it contained. We have already pointed out its connection with the short parable of the fig-tree, which is related for us by St. Luke. In the parable our Lord speaks of Himself as having come three years in succession to seek fruit on the Synagogue of Jerusalem, and as having granted it another year of respite before its final destruction on account of its unfruitfulness. Now the time of respite is at an end, and our Lord signifies the utter rejection of the Synagogue in the cursing of the fig-tree.

This is made the more evident by the circumstances of the miracle. That our Lord may really have been hungry is likely enough, for He seldom allowed Himself much food, and spent the night in prayer, after the day had been spent in teaching, or as was the case with the Day of Palms, in activity which must have naturally exhausted Him. But that He should take occasion to let His hunger manifest itself externally, that He should approach the fig-tree at the season of the year when the figs could not be expected to be there, and then avenge, as it were, His disappointment by cursing the tree instead of making it fruitful before its time to satisfy His need, does not appear very probable.

Intelligence of the disciples

We must seek the meaning of this action in what was represented by it.

He wished then, we may suppose, to signify by some striking external sign, for which He had already prepared the minds of the disciples, that the time for the rejection of the rebellious Synagogue was at hand.

Taken together with the parable, this action meant to say that He had indeed come three years seeking fruit and finding none, that He had thought of cutting it down before, but had been induced by considerations of mercy to wait yet another year, that it might be let alone a little longer, that He might dig about and dung it.

If it had borne fruit, it would have been well. But it had not borne fruit, and it was more than ever obstinate in its unfruitfulness. The time of mercy was past, and the time of chastisement was come.

This could hardly have failed to present itself to the minds of the Apostles when they saw what had happened.

They had witnessed on the day before a great apparent triumph of our Lord, in His entrance into Jerusalem. If what had then passed had raised in them hopes of a change of tone in the Synagogue towards our Lord, this action of His in cursing the fig-tree would at once dispel those hopes. And if they were sorrowfully convinced that the priests would remain as obstinate as ever, this action of our Lord would prepare the disciples for His final breach with the priests, and for the doom of the whole nation.

Thus, if this be the right interpretation of the miracle on the fig-tree, we may see at once how entirely in keeping with the occasion is the teaching which it involves.

Doom of the Synagogue

Our Lord signifies, as it seems, that the time is past during which He would expect fruit from the Synagogue. It was to teem, indeed, with a terrible fruitfulness, in taking the active part which belonged to it in the great sacrifice of His Passion, which was to be the Redemption of the world.

Moreover, between the time at which the sentence was passed, and the time of its final execution in the destruction of Jerusalem and the whole Jewish polity, the utter removal of the Mosaic rites, and the like, there was, in the mercy of God, an interval to take place, nearly the life of one generation, during which many of the children of the Synagogue were to be brought into the participation of the Gospel privileges.

There is nothing more touching in history than the struggle of the Church of Jerusalem under the guidance of St. James and his companions. The annals of that Church are in the main lost to us, on account of the extreme severity of the persecution under which it had to learn. But it cannot be doubted that there were numberless saints and martyrs of the circumcision who might be legitimately reckoned among some of the brightest glories of the first century. So far, the curse of unfruitfulness did not fall at once. Many of the Jews who hung back before our Lord suffered, and even, perhaps, long after, were ultimately numbered among the pillars of the Church.

It is true that, as a system and an organization, the Jewish Synagogue remained always obstinately unfruitful and worse than unfruitful—for it was the great enemy of the Church. The traditions, which lasted into the Middle Ages, of the hatred of the Jews for Christianity, were founded upon historical fact, to some extent exaggerated. The delay in the execution of the full sentence, like the delay in the destruction of Jerusalem, or of the nation, is but an instance of the extreme compassionateness with which God always acts, even in executing vengeance.

The Synagogue was doomed when our Lord uttered His malediction on the fig-tree under the walls of Jerusalem. The actual tree withered down to its roots at the word, and the fate of the community which it represented was sealed, though, ‘for the elect’s sake,’ as our Lord said afterwards, there were years still to pass for souls to be gathered in. And it has been thought by many Christian writers that it was not without meaning, that, at the end of His prophecy about the last days, our Lord has once again brought in the fruitfulness of the fig-tree.

Of this we shall speak more at length presently. It seems as if the sign of the approaching end was, and is to be, this fruitfulness of the fig-tree, which the writers of whom we speak think to be a figure under which the conversion of the Jews of which St. Paul speaks in such glowing terms, is prophetically represented.1

Subscribe now to never miss an article:

The Barren Fig-Tree

See also:

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

St. Matt. xxiv, 32; St. Mark xiii, 28; St. Luke xxi, 29.