Why did the priests tell Pilate that Jesus claimed to be King?

Even in their malice, Christ’s enemies unwittingly declared Him to be King.

Editor’s Notes

The following consists of Father Coleridge’s commentary on the section of the Gospel read on the Feast of Christ the King.

This feast was established by Pope Pius XI in 1925. Its particular focus is on the social kingship of Christ – that is, his sovereignty over society. This is also the doctrine which is called into question in our time. This is why it is such a key theme for traditional Catholics; and why we have written about it many times at The WM Review.

However, while we are reacting to the eclipse of Christ’s social kingship, it is important not to forget other truths that this feast presents.

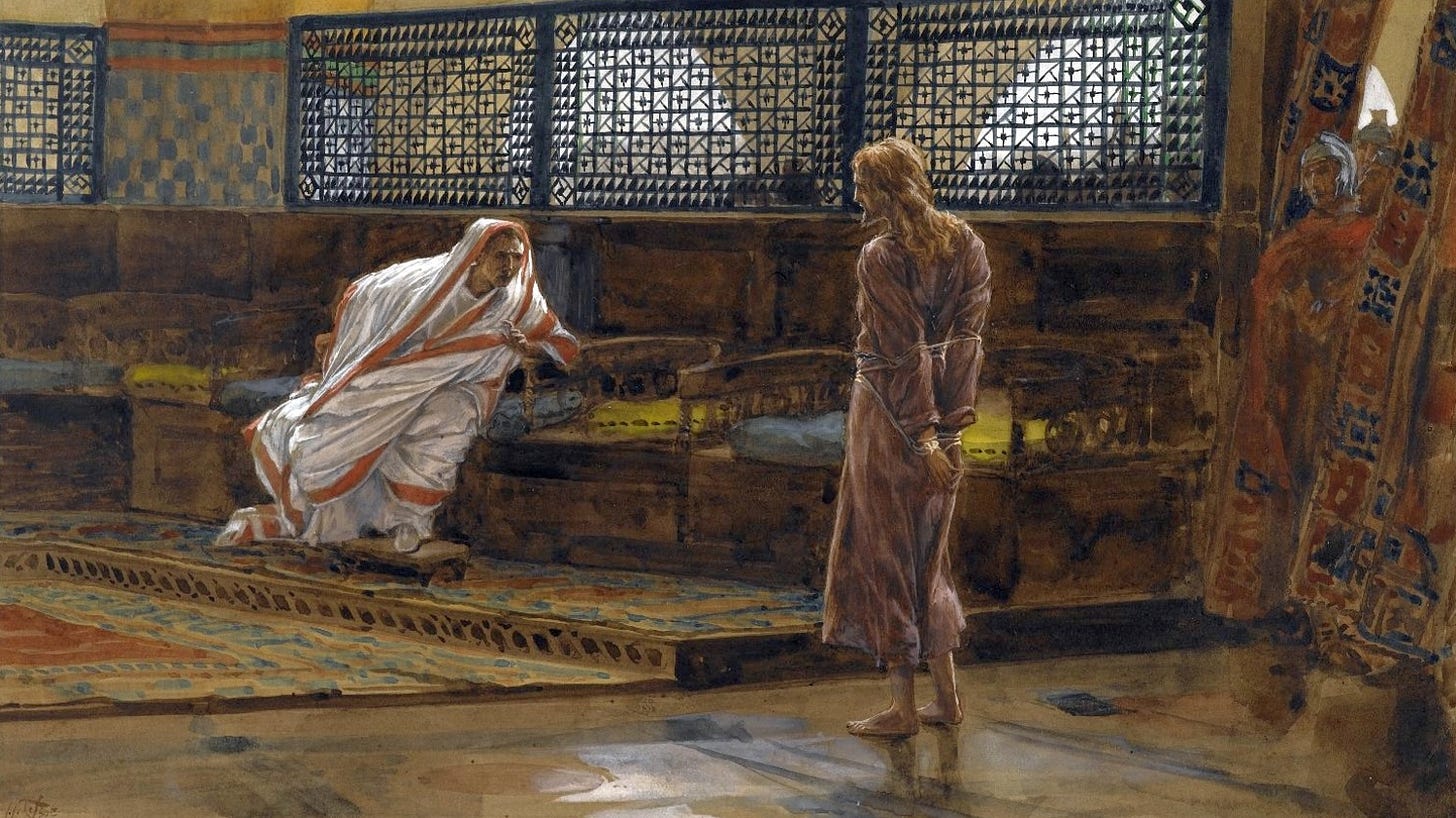

In that vein, the Gospel for the feast presents Christ declaring his kingship before Pilate, and showing what kind of King he really is.

In this part, Fr Coleridge tells us…

How Christ’s Kingship was the very point the priests distorted to bring Him to Pilate.

That the charge of blasphemy was set aside in favour of a political accusation of royal pretension.

Why the world’s Judge was condemned by one who feared Caesar more than the King of kings.

He shows us that Christ’s royal dignity was proclaimed even in the act of handing Him over to death.

See also:

Pilate and Christ the King

The Passage of Our Lord to the Father

Chapter VIII: Pilate

St. Matt. xxvii. 11-25; St. Mark xv. 2-14; St. Luke xxiii. 2-17; St. John xviii. 28-40; Story of the Gospels, §§ 165-167.

Burns and Oates, London 1892.

(Read at Holy Mass on Christ the King)

Why did the priests tell Pilate that Jesus claimed to be King?

Why did Pilate keep asking Christ whether he was really a King?

Pilate himself

The immediate action of the Jewish authorities in the case of our Lord came to an end, as has been said, in the handing over by them of their prisoner, already condemned by them to death, to the Roman Governor, Pontius Pilate.

They were glad in their own minds to have to do this, because, although it was an acknowledgment on their part of their subjection to a foreign jurisdiction, and so far, a humiliation to their pride and feeling of independence, it enabled them to expect that the death of our Lord would be the infliction of the Roman punishment of crucifixion, a more painful and more ignominious death than any permitted by the Jewish code.

Perhaps they were not sorry to have it said that the Man Whom the people had so much honoured had been brought to His end by other hands than theirs.

But our Lord Himself had foretold that He was to die by the hands of the Gentiles for a higher and more Divine reason than the personal spite and jealousy of these Chief Priests. Thus in obedience to the Divine will, as to the manner of the death by which the salvation of the world was to be brought about, these priests themselves were the instruments by whom, as one who was at the time a student in their school at the feet of Gamaliel, pointed out some years after, ‘Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law, being made a curse for us, as it is written, ‘Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree.’1

Thus all the agents in this condemnation of our Saviour to this particular death were co-operating in the deliverance of those under the Law from the burden of the curse which St. Paul mentions in the same passage, ‘Cursed is every one that abideth not in all things which are written in the book of the Law to do them.’

The arrangement of Providence

Much has been said and written on the character of this Pontius Pilate, of whom we have to hear so much in the ensuing history.

He displays himself, as far as we are concerned with him, sufficiently in the accounts of the Evangelists, and we are without any other information on which we can rely. Our interest in him arises from the manner in which our Lord dealt with him, and the patient efforts which He made to do him good.

We may take him as an average Roman, neither better nor worse than others of the class to which he belonged. He had probably a considerable dislike, perhaps a contempt, for the Chief Priests, with whom he must have had many dealings, in the course of which he must have become acquainted with the personal characters of many—their ambitions, their unscrupulousness, their not very correct lives, their use of their great position for their own interests, their animosities, and their profound hypocrisies.

They were not the best specimens of their nation, not the men who might have silently influenced a Pagan of his position to thoughts which might have led him to some better knowledge of the true God, as Cornelius and other heathen with whom we meet in the sacred history seem to have been led. Some of the acts of Pilate, as recorded of him, seem to justify the charges against him of inconsiderate violence and cruelty.

The history shows him as a man of some good instincts and feelings, a man of some amount of natural equity, but not of the moral integrity required in one who had the opportunity of following his instincts of right and justice at the cost of a personal danger to himself.

Pilate a fair specimen of his class—tells the priests to deal with Our Lord themselves

The earlier Evangelists, who tell us all this history in a summary manner, mention simply that the priests and scribes accused our Lord to Pilate of perverting the nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Cæsar, saying that He is Christ the King. This is the account of St. Luke.

It must be remembered that the crime for which the sentence had been passed was blasphemy, but the priests seem to have no scruple in changing the accusation to suit their own convenience, and the apparent chances that they might succeed in making an impression on the Governor. The last Evangelist is here again our fullest authority. St. John’s account is this:

‘Then they led Jesus from Caiphas to the Governor’s hall, and it was morning, and they went not into the hall, that they might not be defiled, but that they might eat the Pasch. Pilate therefore went out to them, and said, What accusation bring you against this Man?

‘They answered and said to him, If He were not a malefactor, we should not have delivered Him to thee. Pilate said to them, Take ye Him, and judge Him according to your law. The Jews, therefore, said to him, It is not lawful for us to put any one to death. That the word of Jesus might be fulfilled which He said, signifying what death He should die.’

The accusation required—not lawful to execute

St. John here throws much light on the history which is imperfect without him. In the first place, we gain from him a new light on the characters of the priests who were so careful to observe ceremonial prescriptions, and to keep up the strict rules about the legal defilements which might be incurred by their violation, at the very time when they were changing the charge on which they expected the Governor to take for granted the justice of a condemnation, which they did not even allege truly, as to the charge on which it had been passed.

They expected Pilate to put in execution a sentence which at this time, at all events, they did not mention. It is clear also that Pilate may have acted very naturally in refusing to accept the simple deliverance of their prisoner to him, as evidence that he must of necessity execute whatever sentence they might have demanded against the prisoner thus handed over to him.

The fact that He was accused of a crime guilty of death not being specified, he simply asks at first, What is the charge?—language required by the circumstances of the case, if he was asked to inflict a punishment, as it was his business to see that it was proportioned to the offence. There is nothing to show that Pilate had any information whether the charge was a capital crime or not. The Evangelist proceeds:

‘They answered and said, If He were not a malefactor, we would not have delivered Him up to thee. Pilate then said to them, Take Him you, and judge Him according to your law.’

This brought out for the first time, as far as we know, the fact that the Jews wished the sentence which Pilate was to carry out at their bidding, to be the sentence of death. The Jews therefore said to him, It is not lawful for us to put any one to death. St. John adds, ‘That the word of Jesus might be fulfilled which He said, signifying what death He should die,’ by which seems to be meant that our Lord had spoken of His death as to be by the hands of the Gentiles, and had even mentioned the death of the Cross.

What was allowed them

Some question has here been raised as to the power of life and death, which is thought to have been reserved from the Jewish tribunals and judges when they came under the Roman power.

The historical evidence is not quite clear on either side of the question. On the one hand, we have this statement, and others which seem to tend to the same conclusion, namely, that the Jewish tribunals had not the power of inflicting ordinarily the penalty of death. On the other hand, St. Stephen was certainly put to death by the Jews, nor is his case quite without parallel, as the death of St. James, the Bishop of Jerusalem, commonly called our Lord’s brother, being His near relative, was certainly brought about in consequence of a sentence of the High Priest at the time, and, it may be added, St. James the Great was put to death by Herod the younger, who put St. Peter in prison also with the intention of treating him in the same way.

But Herod was a favourite of the Emperor, and his powers may have exceeded those ordinarily allowed to the Sanhedrin or the Chief Priests. The question cannot be treated at length in this place. But it may be said briefly that it seems unlikely that the Romans would have allowed the power of death generally to communities like the Jews, or to their priests, or that, if they had, we should not have heard much of it in the Acts, a book which covers a great space of time, during which the Chief Priests were carrying on a relentless persecution against Christians.

But the words of the Jews here may be satisfied—if we suppose that the occurrence of the feast of the Pasch made it indecorous for the priests in this case to execute a sentence of death, as it made it improper for them even to enter the Prætorium of Pilate.

Part II next. Subscribe now to never miss an article:

Pilate

Why did the priests tell Pilate that Jesus claimed to be King?

Why did Pilate keep asking Christ whether he was really a King?

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Twitter (The WM Review)

Galat. iii. 13.